By Fiona Maxwell

The Frances Willard House is one of the first house museums in the United States dedicated to the life and work of a woman. Upon her death in 1898, Frances Willard willed her home to the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. In 1900, the WCTU established its national headquarters in the north side of the house – the “Annex” – and opened the other half as a museum. Anna Gordon, Willard’s personal secretary, was granted life tenancy in the house and was tasked with overseeing its preservation. Gordon sought to maintain a sense of Willard’s presence by keeping the rooms “sacredly intact.”

Over the course of 120 years, the Frances Willard House has served as a residence, a workplace, and a commemorative site. The museum’s audience and purpose, as well as its presentation of Willard’s legacy, have changed dramatically over time. Today, the Willard House emphasizes women’s public activism and professional activities, but during the early twentieth century Willard was portrayed as a saintly woman whose drew strength from her domestic life. Exploring the history of public history at the Willard House reveals the ways in which the commemoration of women’s work has evolved.

What was it like to visit the Frances Willard House Museum in its earliest days? The WCTU’s initial interpretive strategies can be found in the organization’s guidebook to “Historic Rest Cottage,” published in 1911. Visitors to the house museum were assumed to be temperance women with personal and familial memories of Willard. This limited audience shaped the caretakers’ understanding of the purpose of Rest Cottage, and it dictated the ways in which they used its contents to memorialize Willard and promote women’s work.

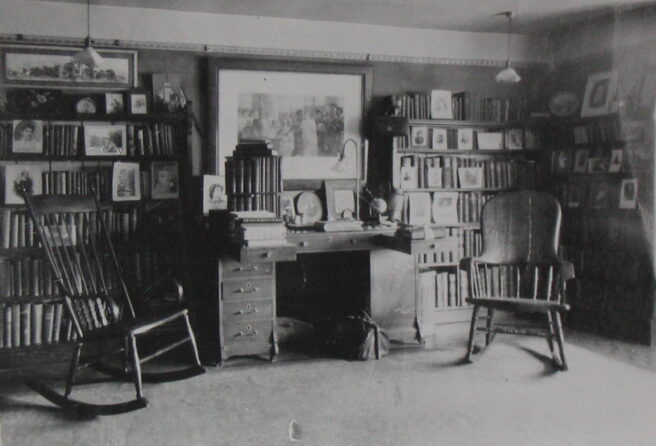

The guidebook narrates a fictional tour taken by a mother and daughter. The mother is a former student of Willard and an “ardent white ribboner,” or temperance activist. The pair “traveled far that she may bring her daughter in touch with an environment which will impress her young life with exalted ideals of service.” The tour begins in the “Den,” Willard’s office, where Willard’s belongings prompted a wave of memories in the mother. While the guidebook uses Willard’s workspace to celebrate “the great organized work against the liquor traffic, led by Miss Willard,” Willard’s activism is characterized as feminine self-sacrifice: “she burned out her life in altruistic service, and ‘made the world wider for women and more homelike for humanity.’” Leaving the office, the visitors “follow in the very footsteps of Frances Willard as she went about her intimate home-life.” The guidebook laments that while Willard’s domestic life was “so simple, so dearly loved,” it was also “so much interrupted by the demands of the work which had first claim upon her.”

The guidebook imbues the house with a sacred aura and presents the tour as a conversion experience. Much attention is devoted to religious paintings, artifacts (including souvenirs once owned by Methodist leader John Wesley), and texts: “Reverently the visitors gaze upon Miss Willard’s Bible and Testament tied with the white ribbon. They are well worn.” After encountering physical objects illustrating Willard’s piety, the fictional daughter turns to her mother and pledges, “You say, Mother, that Frances Willard appealed to the girls to protect the homes and make them what they should be. I wish every girl I know could visit this home. I want to have you put the white ribbon on me before we leave this room because as long as I live I shall work against the liquor traffic and for total abstinence and prohibition.”

The WCTU hoped that a “pilgrimage” to Rest Cottage would cultivate a commitment to Christian temperance in the next generation of “white ribboners.” Meanwhile, for national WCTU officers, Willard’s home served as a boardinghouse and workplace made sacred by the residues of Willard’s presence. The WCTU increasingly credited Willard’s strength and greatness to her home life and believed that the domestic influences of Rest Cottage would continue to shape their work.

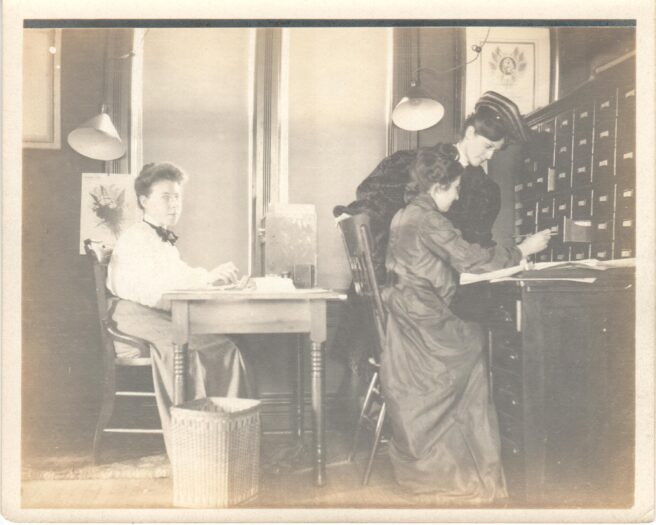

In fact, Willard primarily used Rest Cottage as an office, or as a place of brief respite from her relentless travel schedule. The most consistent resident and head of household was Willard’s mother. The house has been the WCTU’s administrative headquarters much longer than it was the Willard family’s home. The current vision for Rest Cottage seeks to blend its past functions as a workplace and commemorative site by using the house to educate visitors about historical women’s activism. The arrangement of the Den remains much the same as it was during the early 1900s, but docents now use the room to emphasize Willard’s work habits and methods. The Museum has returned the Annex to its turn-of-the-century appearance as the WCTU’s administrative headquarters, transforming it into a staged tribute to women’s professional achievements. The present-day Willard House has moved beyond celebrating one woman’s private life – it now places women’s work at the center of its story.

For a video project that reenacts the early twentieth century Willard House museum visitor experience, please visit our YouTube Channel. To explore the 1911 guidebook, please view this digitized copy.