by Kristin Jacobsen, Assistant Archivist

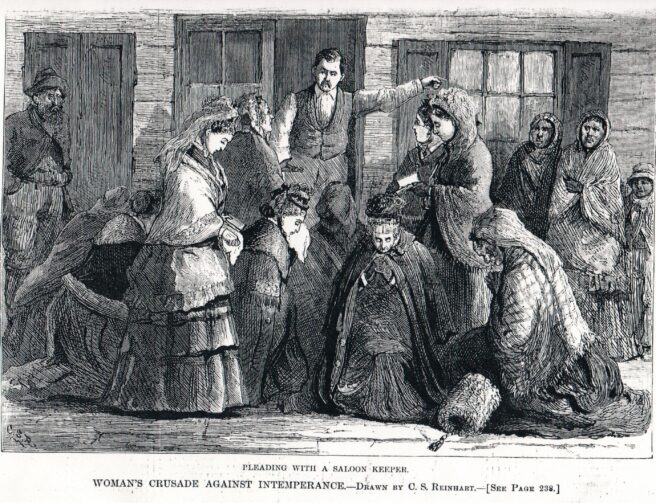

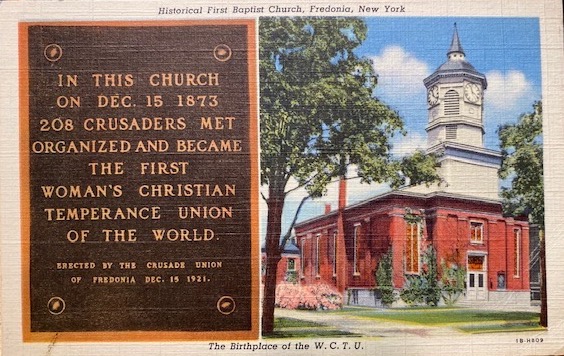

Patrons nursing their beers in the saloons of Fredonia, New York, on December 15, 1873, were met with a startling sight: more than one hundred local women taking to the streets to prevent drinkers from raising another glass. The women visited all eight liquor dealers in Fredonia – praying, singing hymns, and reading from the Bible. Their goal was to convince the owners of bars, drug stores, and hotels to either close or sign a pledge to stop selling alcohol.

It was the beginning of the Women’s Temperance Crusade, an astonishing series of events that took place during the winter of 1873-74 and jumpstarted the largest movement of women up to that time, leading to the founding of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) in late 1874. Though decentralized and organic in its spread, the Women’s Crusade attracted an estimated 50,000 plus women in more than 900 communities in 31 states.[1] Crusaders were mostly white, middle class, and Protestant. Most Crusades took place in in the Northeast and Midwest, and mainly in small towns, although significant events occurred in Chicago and St. Louis.

Ohio Crusaders “capture” a saloon, 1873

Like its medieval European namesakes, the 1873-74 Crusade was driven by religious fervor. Nineteenth-century women Crusaders saw it as their religious duty to correct a major social problem – alcohol consumption. Under the influence of liquor, husbands and fathers became abusive, drank their paychecks, neglected farm work, and brought home sexually transmitted disease. As Annie Wittenmyer, the first president of the WCTU, later wrote, “Surely it was the crowning achievement of the Crusade that it opened the eyes of millions of women and children in this land to the existence and the dangers of the rum-shop.”2

But the activism displayed by the Crusade women was quite shocking. Most white, middle-class women in the nineteenth century confined themselves to the home and to activities appropriate to wives and mothers. Not only was it daring for these women to march into a saloon and engage in protest, it involved risks to more than their reputations. While most owners of saloons, drug stores, and hotels merely argued with the women, some counterattacked by singing and praying at night outside Crusaders’ homes or hiring girls to follow Crusaders around and mimic them. Others responded with violence, including forcibly throwing women out, or dowsing them with dirty water, stale beer, and, in at least one case, the contents of a chamber pot. Some owners went to court to get injunctions keeping Crusaders away from their establishments.3

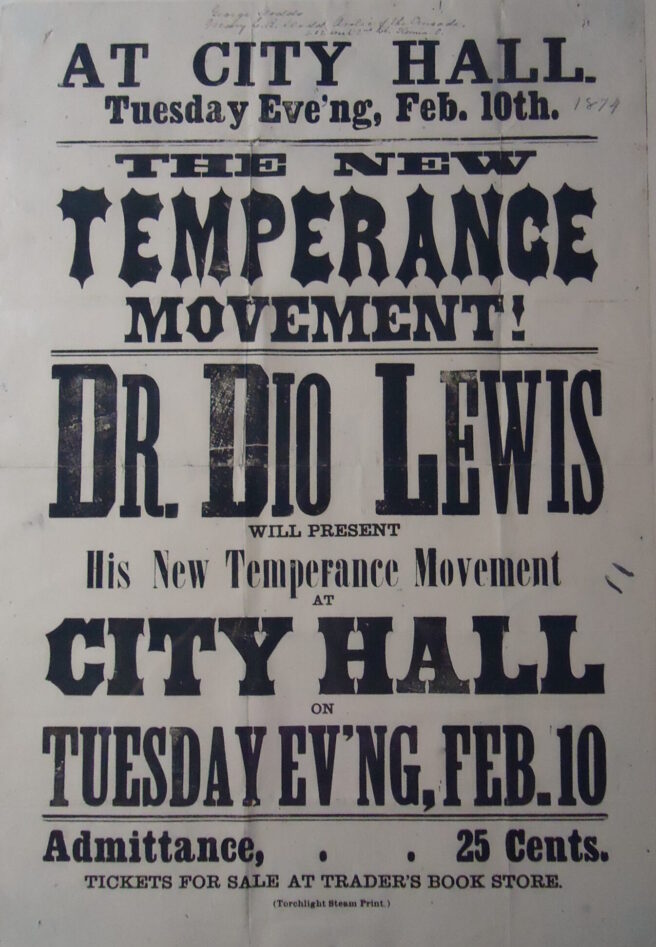

Despite the hazards, women saw temperance work as integral to their roles as guardians of morality and family life. The first Crusaders were encouraged to take revolutionary action by Dr. Dio Lewis, a dynamic lecturer on temperance, sexual chastity, healthy food and exercise, clothing reform, and the rights of women. Lewis told the story of his mother in New York, who prayed, sang, and urged a saloonkeeper not to let her husband drink the livelihood of the family, ultimately convincing him to close. During a lecture in Fredonia, NY, in December 1873, Lewis urged his listeners, nearly a thousand attendees in a town of no more than 2,600, to do the same. Much to his surprise, many of the women in the audience did so the next day—banding together against local alcohol purveyors.

Lewis had given the same lecture hundreds of times, but rarely to such great effect. He travelled to Jamestown, New York on December 16, and gave another lecture. Again, women responded by marching into saloons and drug stores the following day to demand the cessation of alcohol sales. Lewis repeated his lecture on December 23 in Hillsboro, Ohio, and on December 25 in Washington Court House, Ohio. On December 26, “praying bands” of women invaded saloons in both towns.

The women in Washington Court House were the first Crusaders actually to close all saloons and secure pledges from all druggists not to sell alcohol. But Hillsboro, Ohio, though not the first in either chronology or success, became the most famous Crusade. Eliza Jane Trimble Thompson, daughter of an Ohio governor and wife of a well-known judge, was chosen as leader of the Hillsboro group and became celebrated as “Mother Thompson.” Another “Mother” was Crusade leader Eliza Daniel Stewart of Springfield, Ohio.

Like many other spontaneous movements, the Crusade started slowly, built up rapidly, but soon levelled off and declined. After the initial actions in New York and Ohio, the movement spread further afield, fueled by heavy publicity in local newspapers and picked up by metropolitan dailies. The success of a Crusade varied according to how much women were able to accomplish, and for how long. Achievements could include the closing of saloons, a reduction in the number of dealers selling alcohol, or the enactment of local laws prohibiting alcohol sales. Once the Crusaders achieved any of these goals, the women usually disbanded. The shortest Crusades lasted about a month when groups gained an early victory, but without initial success a Crusade might continue for three or four months. Many groups, however, failed to make any dent in the sale of alcohol, and even many of the successes were rolled back when liquor establishments simply reopened after the protests died down.

Dio Lewis gave the movement a boost when he called for a convention, which took place in Columbus, Ohio, on February 24, 1874, and brought together more than 600 women who had engaged in Crusade action or were interested in doing so. But the intensity of the Crusade as a movement could not be sustained, and it was in decline by April 1874.4 Scholars cite loss of support, along with resistance in the community and increasingly aggressive tactics by Crusaders that decreased sympathy for their cause.

Although the Crusade ended, its influence remained strong. A number of Crusaders attended the first National Sunday-School Assembly in August 1874 at Chautauqua Lake in New York, where they told their stories to the wives of preachers in attendance. The women at Chautauqua decided it was time for them to take action, too. They invited existing women’s temperance societies across the country to send one woman from each congressional district as a delegate to a convention in Cleveland, Ohio, to officially found a new national temperance organization that would be run exclusively by women. When the group met on November 18-20, 1874, it elected officers, wrote a constitution, and named the organization the Woman’s National Christian Temperance Union, later revised as the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union.5

The Crusaders knew they had done something of great import. The first president of the WCTU, Annie Wittenmyer, immediately began collecting accounts from Crusaders, and published History of the Woman’s Temperance Crusade in 1878. Matilda Gilruth Carpenter documented the events at Washington Court House in 1893. Frances Willard helped Mother Thompson and her daughters write Hillsboro Crusade Sketches and Family Records, first published in 1896.

Painting in the WCTU Administration Building, Evanston

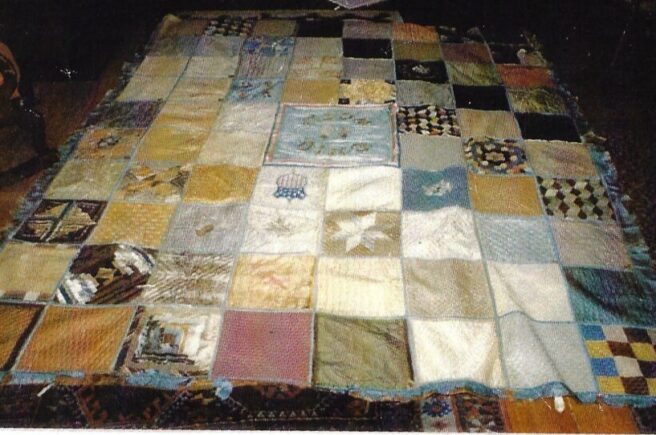

In 1876, an Ohio WCTU leader devised a fundraising plan to create a quilt memorializing both the Crusade and the hundredth birthday of the United States. Unions sent in fabric blocks embroidered or printed with flowers, slogans, and members’ names, donating a dime per member listed. The quilt was given to Crusade leader Thompson and now rests in the Frances Willard House Museum. The center square contained a message that was to remain hidden for a century. Willard is said to have speculated “that the prophecy hidden in the quilt foretold that the licensed saloon would be outlawed, just as witchcraft and slavery had been.”6 The actual message, revealed at the 1976 WCTU convention in Richmond, Virginia, listed the original Crusaders, adding “When 100 years shall have passed… Let Hillsboro be remembered as the birthplace of the Crusade and may… all whose names this record bears, live forever.”7

In these and many other ways, the Women’s Temperance Crusade of 1873-74 has continued to serve as a symbol of women’s courage and innovation in the fight against alcohol, tobacco, and drugs, and as the founding impulse of the WCTU. On the WCTU’s one hundredth anniversary in 1974, national president Ruth Tibbets Tooze wrote that “The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union sprang from the brain of women of the Crusade. The whole work had the force of a mountain avalanche, hopefully to forever destroy the power of the liquor traffic. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union abandoned the methods but never the principle of the Crusade.”8

Note: primary-source documents and images for this essay come from the files, photo collections, artifacts, and publications in the Frances Willard Memorial Library and WCTU Archives.

Footnotes

1. Scholars’ estimates of the number of participants range between 32,000 and 142,000. For statistics, see Jack S. Blocker, “Give to the Winds Thy Fears”: The Women’s Temperance Crusade, 18731874, Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 1985: 24-25; and Jed. Dannenbaum, “The Origins of Temperance Activism and Militancy among American Women,” Journal of Social History 15, no. 2 (Winter, 1981): 235.

2. Annie Wittenmyer, History of the Woman’s Temperance Crusade: A Complete Official History of the Wonderful Uprising of the Christian Women of the United States against the Liquor Traffic, which culminated in the Gospel Temperance Movement, Boston, Mass.: Published by James H. Earle, 1882: 15. Though it seemed to come out of nowhere, the Women’s Crusade was the culmination of many decades of women’s involvement in temperance efforts. Temperance began as a national movement in U.S. in the 1820s. Women were involved from the beginning, but they stepped up in large numbers beginning in the 1840s – joining Martha Washington societies (sister to the men’s Washingtonian societies), and a few years later the Daughters of Temperance (to the men’s Sons of Temperance) and the Independent Order of Good Templars. After the Civil War, with alcohol use increasing sharply, saloons doubled between 1863 and 1873, beer consumption tripled, and whiskey intake increased by fifty per cent. Women also supported the 1869 formation of the Prohibition Party, which put forth a presidential candidate in 1872. Across the country, local Women’s Temperance Leagues were formed. For background, see Dannenbaum, 235-246; Ruth Birgitta Anderson Bordin, Women and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873-1901, New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990: 5; Eugene O. Porter, “An Outline of the Temperance Movement,” The Historian 7, no. 1 (Autumn, 1944): 58-59. For statistics, see John Holley Clark, Jr., “The Prohibition Cycle,” The North American Review 235, no. 5 (May 1933): 417.

3. Blocker: 59-77.

4. Blocker, 19-20.

5. Frances Willard, who became the second president of the WCTU in 1879, had little direct involvement in the Crusade; at the time, she was the Dean of Women at Northwestern University in the dry town of Evanston, Illinois. She did participate in a visit to a saloon in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania later in 1874.

6. Hayes, Mrs. Glenn C., “The Mystery Quilt,” The Union Signal (August 1976): 10.

7. Detwiler, “Crusade Quilt” [transcription of message sewn into a center quilt block], “Crusade Quilt” subject file, WCTU Archives, Evanston Illinois.

8. Mrs. Fred J. [Ruth Tibbets] Tooze. “President’s Address: Unlimited Horizons.” In Report of the One Hundredth Annual Convention of the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union. Cleveland, Ohio, 1974: 54.

Further Reading

Primary Sources: Books (most available online from Internet Archive or HathiTrust)

Carpenter, Matilda Gilruth. The Crusade: Its Origin and Development at Washington Court House and Its Results. Columbus, Ohio: W.G. Hubbard, 1893.

Stewart, Mother [Eliza Daniel]. Memories of the Crusade: A Thrilling Account of the Great Uprising of the Women of Ohio in 1873, Against the Liquor Crime. Columbus, Ohio: W. G. Hubbard & Co., 1888.

Thompson, Eliza Jane Trimble, et al. Hillsboro Crusade Sketches and Family Records. Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham, 1906.

Willard, Frances E. Glimpses of Fifty Years; The Autobiography of an American Woman. Chicago [etc.]: Woman’s Temperance Publication Association, 1889.

Wittenmyer, Annie. History of the Woman’s Temperance Crusade: A Complete Official History of the Wonderful Uprising of the Christian Women of the United States against the Liquor Traffic, which culminated in the Gospel Temperance Movement. Boston, Mass.: Published by James H. Earle, 1882.

Secondary Sources

Blocker, Jack S. “Give to the Winds Thy Fears”: The Women’s Temperance Crusade, 1873-1874. Westport, Conn: Greenwood, 1985.

Bordin, Ruth Birgitta Anderson. Women and Temperance: The Quest for Power and Liberty, 1873-1901. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1990.

Dannenbaum, Jed. “The Origins of Temperance Activism and Militancy among American Women.” Journal of Social History. Vol. 15, No. 2 (Winter, 1981), pp. 235- 252.