By Fiona Maxwell, Director of Museum Operations and Communications; PhD candidate in History at the University of Chicago

“Look up and off, and on and out; it is the curse of life that nearly everyone looks down.” – Frances Willard

By 1874, Frances Willard had acquired a local reputation as a public speaker. Yet, when she began giving temperance addresses in Chicago churches that were “packed with people,” she recalled feeling “frightened by the crowd and overwhelmed by a sense of my own emptiness and inadequacy.” After one event, she overhead a male minister calling her speech “a school-girl essay” because she had read it from a script. Angry and ashamed, that night she vowed to “never again appear before a popular audience manuscript in hand.”

When Willard entered the political arena during the 1870s, she built on the progress made by previous generations of women reformers, who had secured women the right to address mixed-gender public audiences. Nevertheless, many conventions continued to constrict the performance practices available to women speakers. One stubborn custom was that men delivered memorized orations and looked out into the audience, while women read essays from the manuscript and kept their eyes lowered.

As a “Western” woman, Willard enjoyed unusual freedom and acceptance as she pursued speech training and made her initial public appearances. She studied with Robert Cumnock, Northwestern’s elocution instructor and founder of the Cumnock School of Oratory, who was committed to training women in all speaking genres. While Willard celebrated Evanston as a “paradise for women,” she described East Coast audiences as “conservatives” who were unaccustomed to women speakers. One woman from Maine recalled that Willard was the first woman she ever heard speak in public. Some New Englanders were unwilling to hear women at all. When Harvard students invited Willard to speak, the university’s president Charles William Eliot canceled the event “because he didn’t believe in women appearing in public.” Reacting to this injustice, a Northwestern student editorialist snapped: “You had better wake up, Mr. Rip Van Winkle.” Even in the Midwest, however, the idea that women should keep their eyes on a script persisted. In 1870, a graduating senior at Oberlin shocked her Commencement audience by lifting her eyes from the page.

Willard encouraged women to break this tradition. When she became the first Dean of Women at Northwestern, she remembered that the idea of young women “participating in debates with young men, and making orations, was unheard of.” Seeking to serve as a role model, Willard gave weekly speeches on political topics at the Women’s College. She also convinced university president Erastus Haven that allowing women students to give orations at coeducational literary society meetings would help “break down the prejudice against woman’s public speech and work.” In terms of women’s oratorical training, Northwestern became one of the most progressive institutions in the country.

Following Willard’s example, women students at Northwestern began to discard their manuscripts. Willard had so thoroughly changed Evanston public opinion that male student reporters encouraged women to memorize. In 1876, “Miss M. E. Bradshaw” received accolades for breaking convention at the Junior Exhibition. Her oration was deemed “among the best of the evening,” the student newspaper effused, “and we think the lady showed good judgment by dispensing entirely with her MS [manuscript].” Her fellow performer, Elizabeth Hunt, was advised that her “production would have had a better effect upon the audience had she followed the example of Miss Bradshaw in regard to her MS.” Hunt took the hint. The following year, she competed in Northwestern’s male-dominated oratorical competition, earning an unusual honorable mention for her memorized performance. Then, at Commencement, she looked out into the audience and, with “self-possession and naturalness,” gave “a thoroughly excellent and original oration.” She went on to appear on the platform alongside Frances Willard at meetings of the Western Association of Collegiate Alumnae and was eventually hired as the Head Instructor in English and Rhetoric at the Cumnock School of Oratory. Through this position, Hunt, like Willard before her, helped women students “prepare themselves more fully for the exacting demands of Public Reading.”

Later, as president of the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Willard established a system by which women across the country could overcome societal constraints, as well as their own insecurities. In the early days of the WCTU, “very few” members “could make a speech,” Willard recalled. Instead, they gave “speechlets”: “off-hand talks of from five to fifteen minutes.” By presiding over meetings and conventions, women soon acquired new abilities and confidence. The WCTU also trained girls and young women to build speaking skills early in life: members of the Young Woman’s Christian Temperance Union and the children’s Loyal Temperance Legion memorized and performed poems, dialogues, speeches, and original essays. By the 1890s, Willard stated proudly that “nearly all” WCTU workers had “learned to speak acceptably in public without manuscript or notes.”

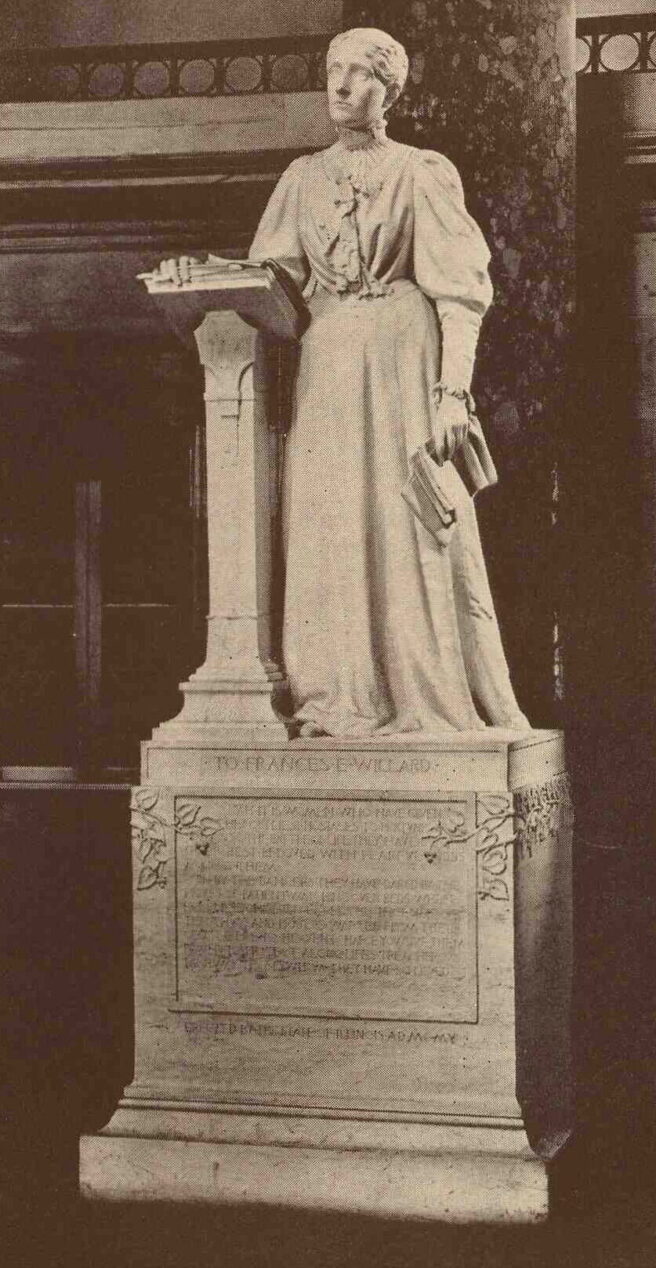

In a world where women were expected, and often forced, to “look down,” Frances Willard inspired women to “look up and off, and on and out.” As part of her “Do Everything” leadership model, she cultivated an international network of women reformers, performing artists, and teachers who worked to ensure that girls and women were able and confident to face their audiences and make their voices heard.