By Janet Olson, CWHL Archivist.

[Part three of a series]

We mean 1874, of course! It was a time of change, endings and beginnings, for Frances Willard and the temperance movement in Evanston.

- In June, Willard resigned from Northwestern University, ending her official teaching career.

- In August, a number of Evanston women (not including Willard) journeyed to upstate New York with their Methodist minister husbands to attend a retreat at Lake Chautauqua, where they discussed forming a national organization to work for temperance.

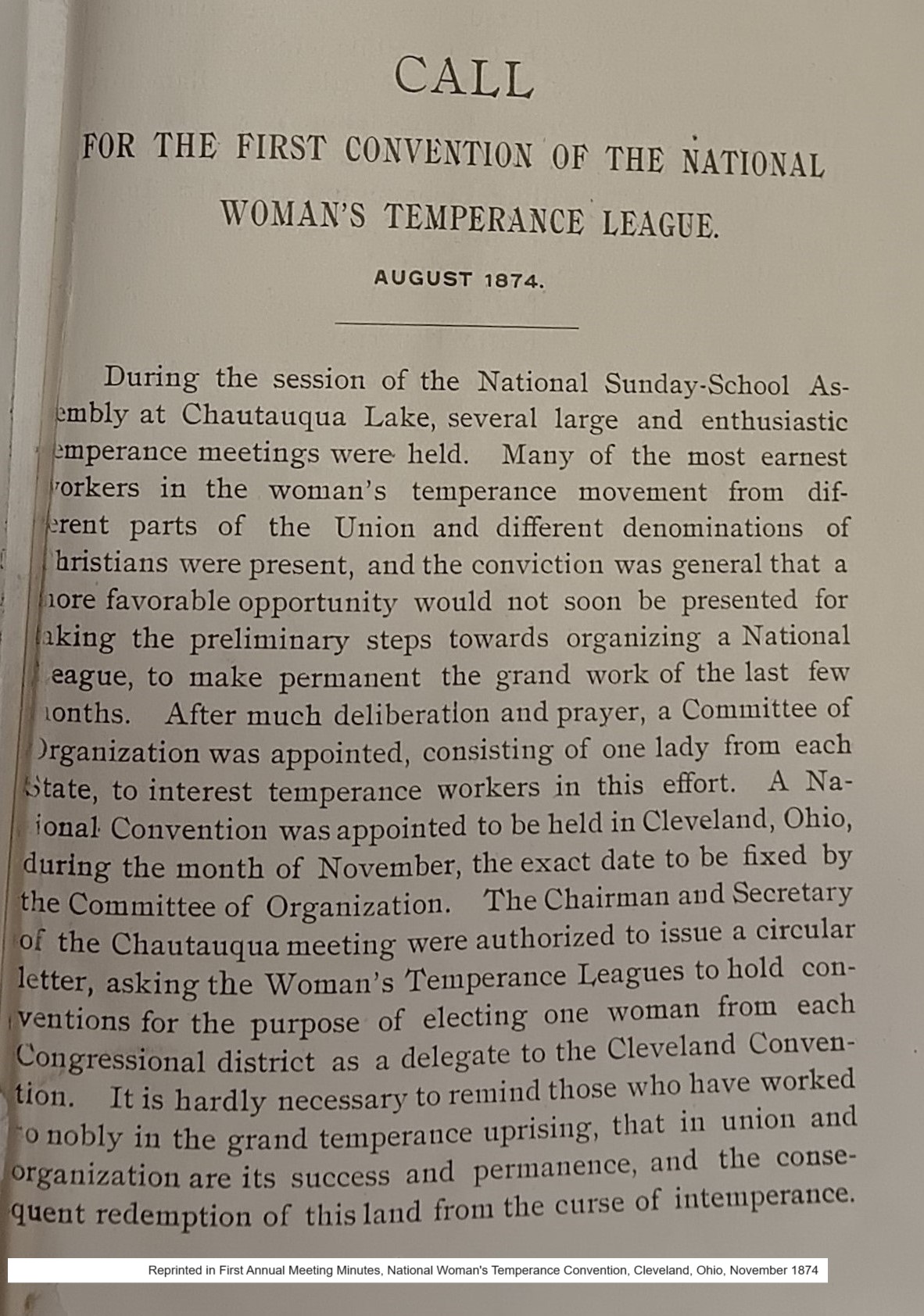

- And as summer turned into fall, the idea of a national woman’s temperance organization ripened into the first official convention—held in Cleveland, Ohio, in November–of what would become the WCTU.

Willard Leaves Northwestern University

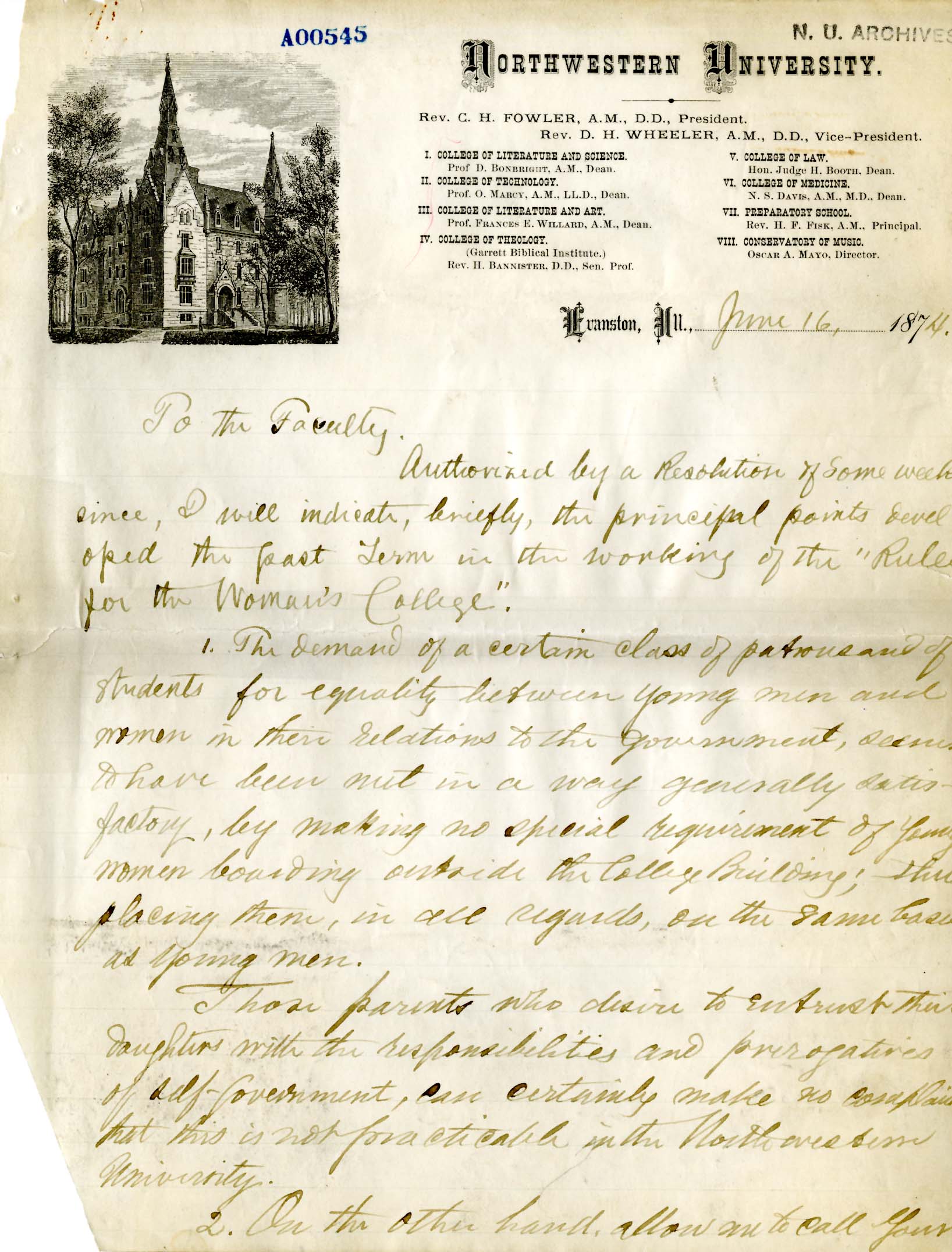

Willard’s resignation from Northwestern came after a year of difficulties.[1] In June, 1873, when the Evanston College for Ladies (with Frances Willard as president) merged with Northwestern University, Willard was no longer president of a woman’s college, but was named Northwestern’s first Dean of Women (she was also appointed to a full professorship of Aesthetics). However, the new president of Northwestern, Charles Fowler, although a true believer in coeducation, was not as concerned as Willard was about separate supervision for women students. With the merger of the two institutions, it became clear that Willard’s role did not give her the authority she needed to assuage parental worries and build strong, self-reliant women. Despite support from her students and from the women on NU’s Board of Trustees, Willard turned in her multi-page resignation letter on June 16, 1874. (She continued her interest in Northwestern, and herself served on the Board of Trustees in later years.)

The Evanston Woman’s Temperance Alliance

When last we saw the intrepid members of the Evanston Women’s Temperance Alliance, they were busy going door to door “pledging the town” to ensure that Evanstonians were on board with temperance.[2] They were also establishing ways to deal with local scofflaws who were selling liquor and permitting smoking and gambling. The Index reported that the woman’s Temperance Alliance,

“appreciating the embarrassment systematically thrown in the way of all who attempt to prosecute the secret and open venders of intoxicants…[has] created a committee of vigilance[3] consisting of many influential ladies and gentlemen whose duty it will be to attend the courts, to prevent…the intimidation of witnesses and to do whatever else may be necessary to ensure a prompt and vigorous prosecution of all violators of the University charter law and the laws of this state and village within reach of the influence of the Alliance.”[4]

Despite the ferocity of this statement, a later meeting clarified the organization’s intent. Mrs. Arza Brown and Mrs. Moore were chosen as a “Judicial Committee” to determine what legal rights and privileges the women of the Alliance had “in protecting women who suffer from the evils of rum.” It was stressed that the goal of the Alliance was not to get involved in lawsuits, “but more particularly to create moral sentiment in favor of temperance, to induce all residents to sign the pledge and save our children from becoming addicted to the vice of intemperance.”[5] These two reports show that the Evanston Woman’s Temperance Alliance was still making front-page news in its local campaign. By the end of the summer, inklings of a national organization would change the prospect.

The First Chautauqua

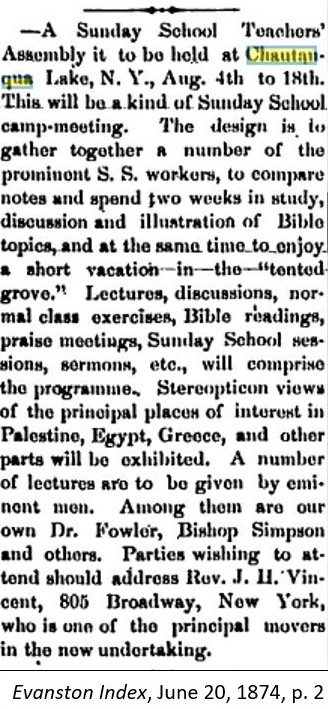

In June, 1874, Evanstonians saw an announcement for an August gathering in upstate New York. Founded by Methodists as the Chautauqua Lake Sunday School Assembly in Chautauqua, NY, it was an experiment to offer an educational and retreat experience for ministers and Sunday School teachers—and their wives.[6]

Although Willard did not attend the event (August 4-18), a significant number of Evanstonians were there, and a few women (including Emily Huntington Miller and Jennie F. Willing) spoke. Other attendees included women who had participated in the Temperance Crusades the previous winter/spring. Recognizing the limited success of the ad-hoc Crusades, the women discussed founding a national, permanent, all-woman temperance organization, and left the summer retreat with a plan to convene an organizational meeting in the fall of 1874.

Frances Willard Finds Her Vocation

Back in Evanston, Willard was becoming reconciled to her departure from NU, which she had at first described as “the greatest sacrifice my life had known or ever can know.” Later she would write that “I can not truthfully say I left the Deanship of a college and a professor’s chair in one of America’s best universities on purpose to take up temperance work… It is however true, that having left,… I had, at last, found my vocation, that is all, and learned the secret of a happy life.”

When the call came for women to attend the organizing convention in November, 1874, at the Second Presbyterian Church in Cleveland, Willard joined several other Evanston women (including those who had been at Chautauqua). Willard was elected the first corresponding secretary of what was at first called the National Woman’s Temperance League. (Nov 17-19, 1874).

The Rest Is History!

The next installment of this series will talk about the first WCTU convention and the further activities of the Evanston Woman’s Temperance Alliance.

During 2024, to mark the 150th anniversary of the founding of the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (November, 1874), we are shining a local spotlight on the Evanston women (and men) who were “early adopters” of the temperance campaign. This joint project of the Evanston Women’s History Project and the Center for Women’s History and Leadership draws upon the many historical resources available in Evanston to address the rhetorical question that WCTU member Jennette Hauser posed in 1883: “What is the use of a temperance society in Evanston, where the sale of liquor is already prohibited?”

[1] For more about Frances Willard as Dean of Women at NU (part of the Educated Women blog series), see https://cwhlevanston.org/educated-women-part-three-dean-frances-willard/ and “On the Same Terms: The beginning of co-education at Northwestern”

[2] For the Evanston Woman’s Temperance Alliance and “Pledging the Town,” see https://cwhlevanston.org/pledging-the-town/

[3] “Vigilance Committees”—groups of private citizens administering law and order–would have been a familiar concept to Evanstonians of this era, who were referring to the term’s original use by abolitionists of the 1830s-50s who assisted fugitive slaves; later, though, the term was adopted by vigilante groups which attacked minority groups.

[4] Evanston Index, April 11, 1874, p1

[5] Evanston Index, May 16, 1874, p1

[6] Chautauqua, later called the Chautauqua Institution, was based on the retreat/revival model of summer camps on Martha’s Vineyard and other Protestant religious gatherings in inspiring, bucolic settings. The New York Chautauqua was a success from the beginning. It immediately expanded to include self-improvement opportunities through art, music, lectures and the nation’s oldest book club. There continued to be a strong WCTU presence at Chautauqua for many years. The NY location and the many spin-off Chautauquas across the country continue to attract attendees of all ages and faiths.

For more about the first Chautauqua and the inspiration for the WCTU, see Kristin Jacobsen’s blog post at https://cwhlevanston.org/birth-of-the-wctu-temperance-women-ride-a-national-wave/ Note that the Chautauqua Institution is also celebrating its 150th anniversary in 2024! Congratulations, https://www.chq.org/