March is Women’s History Month and this year we are thinking about the places where women’s history happened, why it is so important to preserve them, and how easily they can be lost and forgotten. In advance of our program (Sunday 3/28 at 4 pm) – A Conversation with Michelle Duster: author of Ida B. the Queen – a reflection on Wells’s presence (or lack thereof) in the landscape of historic places and monuments seemed appropriate.

Note: if you missed the program you can watch the recording on our YouTube Channel here.

In her book, Duster reflects on the work of rescuing her great-grandmother’s story. Duster and her extended family have spent countless hours ensuring that Wells is not forgotten, and they’ve done so in a myriad of ways – including recovering and republishing her writings; advocating for historic markers at locations where she lived and worked; and getting involved in and creating monuments, sculptures, and even street signs to honor her.

There is a museum for Wells in Holly Springs, Mississippi where she was born and raised. But there is no museum in Chicago for her – where she lived and worked for almost all of her life. Her house is thankfully protected as a Chicago Landmark and listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The 2017 renaming of Congress Parkway to Ida B. Wells Drive was a significant addition to the list of places named for her. A new monumental sculpture will be unveiled this year in Chicago’s Bronzeville neighborhood, and a new mural project that will include her (along with other Illinois suffragists) is planned for Chicago’s loop.

But there is one important place from Wells’ story that is truly lost from the landscape – the building that housed the Negro Fellowship League and the Alpha Suffrage Club. This building was located at 3005 S. State Street in a neighborhood filled with black-owned homes, businesses and organizations. This neighborhood is slated to become the new Bronzeville-Black Metropolis National Heritage Area to provide some protection for what remains. But the Negro Fellowship League building is long gone.

Wells and her husband, Ferdinand Barnett, started the Negro Fellowship League in 1910. It was meant to provide support, including a library, housing and employment services, to newly arrived immigrants from the South. Patterned after a settlement house, the League building functioned as a community center for the growing Black population. In January 1913, Wells organized the Alpha Suffrage Club, which met at the League building.

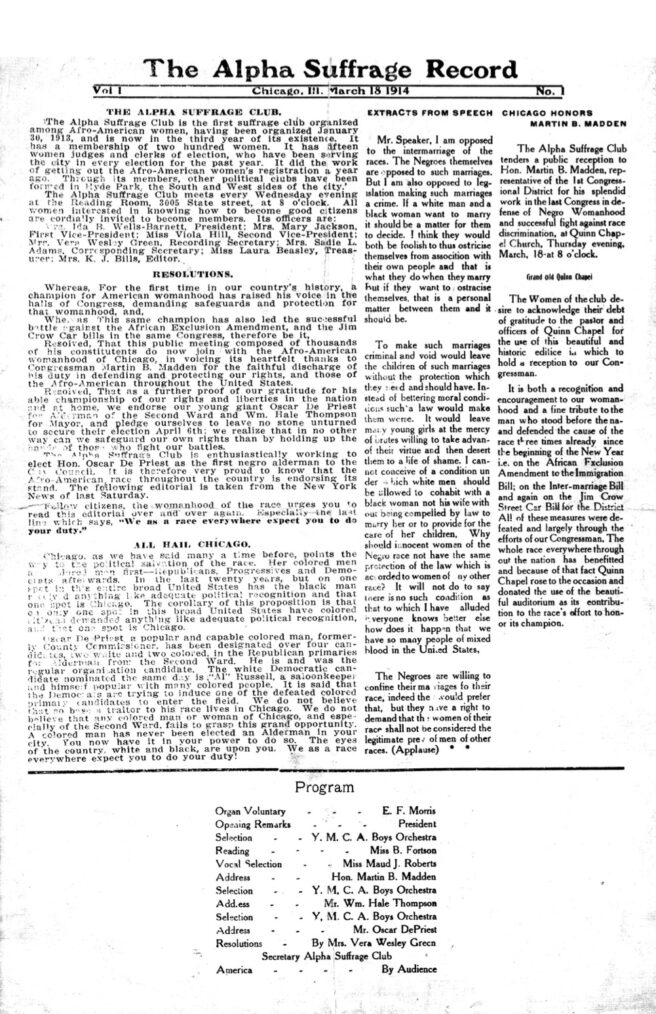

The Alpha Suffrage Club was formed by Wells to give Black women a voice in the Illinois suffrage movement at a time when the state legislature was considering granting Illinois women the vote. One of the first actions of the club was to raise money for Wells to travel to Washington D.C. as part of the Illinois delegation to the March 1913 national suffrage parade. Wells’s protest of the segregation of the parade marked a key moment for the state and national suffrage movement.

In June of 1913, Illinois women gained the right to vote in all elections not prohibited by the state constitution (including presidential electors). This new power kicked Wells and the Alpha Suffrage Club into high gear. They utilized a new “block system” to canvass neighborhoods and register new women voters. In 1914, due to the club’s work and the overwhelming participation of women in the election, Chicago gained its first Black Alderman, Oscar de Priest. De Priest went on to become Illinois’ first Black Congressman.

The importance of the Alpha Suffrage Club to the women’s suffrage story became apparent in the lead up to the 100th anniversary of the 19th amendment in 2020. We made sure that its location was added to the National Votes for Women Trail and we are continuing to work to install a historic marker there. But how much better it would be to have the original building present, rather than a vacant parking lot.

At the Willard House, we know how fortunate we are that the house and its story have been preserved all these many years. The story of the Alpha Suffrage Club reminds us just how challenging this work of preserving women’s history is – and is a cautionary tale for working hard to preserve what we have left.

I hope you will consider making a gift to support the work of preserving and telling these stories at the historic places that hold them.

Thank you!

Lori Osborne, CWHL Executive Director