By Kristin Jacobsen, WCTU Archives, Archives Assistant

In mid-August, 1874, a group of temperance women came together to seize a national moment that led to formation of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU). The women were wives of a group of Methodist clergymen who were attending the first National Sunday-School Assembly at Chautauqua Lake in upstate New York.

The ten-day Assembly was part camp meeting, part Sunday School teacher training, part retreat, held in an idyllic, forested setting. Soon renamed the Chautauqua Institute, the Assembly would usher in its own national movement as a pioneer in the trend toward adult education and self-improvement. The annual summer Chautauqua “season” eventually offered lectures, classes, concerts, and other activities incorporating both religious and secular topics. It would be the first to offer a national correspondence school, the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle (CLSC), which gave adults in isolated areas the opportunity to take courses and graduate from the CLSC. “Daughter Chautauquas” would also develop, bringing educational and cultural experiences to small towns all over the U.S. and Canada.[1]

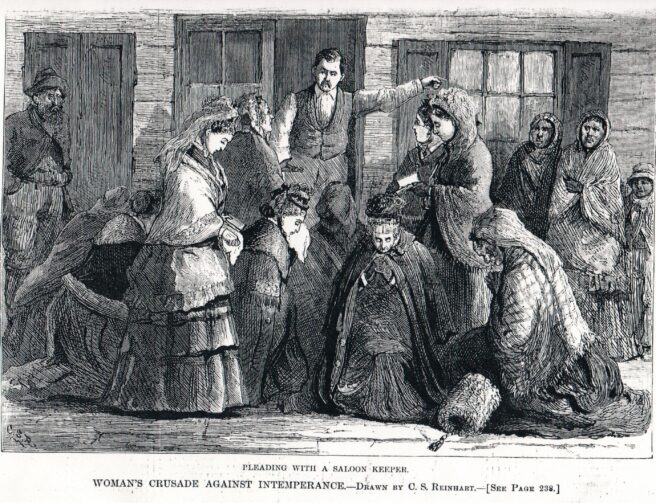

In summer, 1874, these developments were yet to come. The issue on the minds of the women who met at that first Chautauqua were the events of the previous winter, when “praying bands” of temperance women in New York and Ohio led what came to be called the “Women’s Crusades” against alcohol. Inspired by health and temperance activist Diocletian Lewis’ speeches, women left their homes to pray and sing in front of saloons and drug stores in order to pressure owners to give up selling alcohol as drink or medicine. The tactic was not new, and its success short-lived, but the speed with which the Crusades spread and the extent to which they were publicized led temperance supporters to realize that this was a pivotal moment in history.

That summer, when Crusade participants attended the Assembly at Chautauqua and told their stories, the clergymen’s wives decided it was time for them to take action, too. Although Frances Willard was not in attendance at this first gathering, she recounted Ohio attendee Mary Ingham’s description: “One bright day a very few ladies were in conversation upon the subject that filled their hearts, inspiring the thought that the temperance cause needed the united effort of all the women of the country … and it was said: ‘Why not take steps right here toward its formation?’ Upon further consultation it was decided to call a meeting of the ladies….”[2] The women were convinced, Willard later wrote, that “a more favorable opportunity would not soon be presented for taking the preliminary steps toward organizing a National League, to make permanent the grand work of the last few months.”[3] The women met first on August 14, 1874, to select representatives from various states to make more formal plans the next day.[4]

On August 15, the women met under the Assembly’s big canvas tent, with men watching and supporting but not participating: officers and members of the new organization would exclusively be women. They elected a chair, a secretary, and a committee of organization with representatives from each state to generate interest in the endeavor. The chair and secretary were authorized to circulate a letter inviting existing Women’s Temperance Leagues across the country to elect one woman from each congressional district as a delegate to a convention in November to officially found the new organization.

Between November 18 and 20, 1874, the duly elected delegates convened at Cleveland’s Second Presbyterian Church. Men were again present only to watch and make a few speeches. They were “relegated to the ‘Amen corner’ and warned not to interfere.”[5] The officers and delegates to the convention set up twelve committees (later to be called Departments of Work), wrote a constitution, and named the organization the “Woman’s National Christian Temperance Union.” Elected officers were Annie Wittenmyer of Philadelphia, PA, president; Frances E. Willard of Evanston, IL; corresponding secretary; Mary C. Johnson of Brooklyn, NY, recording secretary; and Mary Ingham of Ohio, treasurer. They had ambitious plans, as Willard summarized:

“Something practical” is what our people clamor for, and justly. Well, we have here a plan of organization that is meant to reach every village and hamlet in the Republic; a declaration of principles of which only Christ’s religion could have been the animus; an appeal to the women of our country, another to the girls of America, and a third to lands beyond the sea; a memorial to Congress, and a deputation to carry it; a National Temperance Paper, ‘of the women for the women…’.”[6]

The new organization, later renamed the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, went far beyond what its founders could have imagined it would achieve. As its second president, from 1879 to 1898, Willard expanded the work of the WCTU to include broad social reform and political change, what she called her “Do Everything” policy. Women and girls across the nation and around the world were empowered to take action in their communities. The WCTU went on to help pass the 18th amendment prohibiting alcohol, and the 19th amendment granting women the right to vote.

Meanwhile, the WCTU continued to have a strong connection with Chautauqua. Willard went to Chautauqua in 1875 to report on the temperance organization’s progress. She was also the first woman to give a lecture at Chautauqua, in 1876, setting a precedent followed by notable women from Susan B. Anthony to Eleanor Roosevelt. Many WCTU members made annual summer trips to Chautauqua, and a WCTU union was formed there.[7]

Rooms in Kellogg Hall, one of Chautauqua’s iconic structures, were set aside for the WCTU. Built by James Kellogg to honor his mother, Annie Kellogg, who was both a WCTU member and a graduate of Chautauqua, the building was dedicated on August 15, 1889, the fifteenth anniversary of the WCTU’s origins. An ornate stained-glass memorial window to Willard was installed in Kellogg Hall in 1904. To commemorate the WCTU’s 50th anniversary in 1924, WCTU President Anna Gordon bought a house at Chautauqua, known first as the Frances Willard House and later as Temperance House. The Willard window from the Kellogg house was moved into the new space, and an Italian stone drinking fountain was placed in front of the house. When the WCTU sold Temperance House to private owners in 1946, the stained-glass window was moved to Evanston, where it was installed in the WCTU Administration Building.

Looking back 146 years later, we can see just how much political and social impact resulted from the founding meeting of WCTU at Lake Chautauqua. Although the founders could not foresee how the organization would affect not just alcohol policy but also the lives of women, they recognized their unique opportunity to build upon the national attention that the Women’s Crusades had aroused. By leveraging the passion and sense of purpose of their historic moment, they inspired others to join in agitating for change.

For more information, see “History of the WCTU” https://cwhlevanston.org/frances-willard/history-of-wctu/.

[1] The Chautauqua Institution in New York and many of its “daughters” still exist, still offering culture and education. For more about the Chautauqua Institution’s history, see https://chq.org/about-us/history

[2] Frances E. Willard, Woman and Temperance: Or, The Work and Workers of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, Sixth edition, 1897, 126; from Minutes of the WNCTU, 1874-77, p 3-4. See Crusades subject file, WCTU Archives, 122.

[3] Ibid., 126.

[4] Ibid., 122-125.

[5] Norman H. Clark, “Women’s Christian Temperance Union Convention,” Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. https://case.edu/ech/articles/w/womans-christian-temperance-union-convention.

[6] Willard, 135.

[7] The Chautauqua Institute was dry from its origins. Its restaurants would only begin to offer alcoholic beverages in the late1990s, although residents could drink in their own homes.