By Janet Olson, Archivist

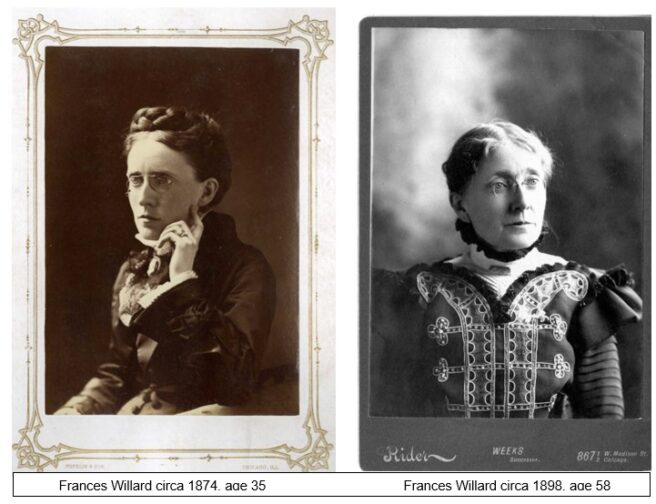

When she died in 1898, Frances Willard was known across the United States and around the world. Willard had been president of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU)since 1879, five years after the organization was founded. Under her leadership, the WCTU’s mission had expanded to include woman suffrage and social reforms that would address the causes of alcoholism. The WCTU itself had grown to over 200,000 members globally. As she approached the age of 59, Willard was famous. She was also worn out and ill.

Aside from Frances Willard’s mother, the other members of the small family had died long ago. Her mother’s death in 1892 at age 87 was devastating for Willard, who lost her most faithful supporter. Mrs. Willard died of pernicious anemia, and soon afterwards, Frances Willard began to exhibit symptoms of the disease herself. There was no cure known at that time, and Willard’s lifestyle, with its constant traveling, speechmaking, and stress, allowed her little time to rest and rebuild her strength. It was sadly ironic that someone known for her persuasive oratory would suffer from an illness that caused her tongue to swell painfully.

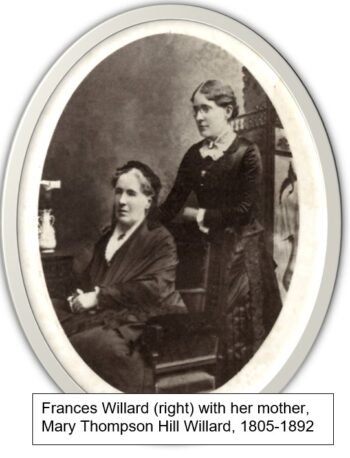

Willard tried alternately to ignore her illness and to combat it. She began to spend a good deal of time in England, where her British counterpart, Lady Henry Somerset, offered her a restful retreat. Somerset also encouraged Willard to exercise to build up her strength. She hired what we would now call a personal trainer, who worked with Willard in Somerset’s home gymnasium. Always interested in new health trends, Willard became a vegetarian–probably not the best idea for someone with anemia. And she famously learned to ride a bicycle at age 53.

In January 1898, Willard was in New York City, where she was fundraising for the WCTU headquarters building in Chicago. She had planned to travel on to England once again but came down with pneumonia. In her weakened state of health, she could not recover. She knew the end was near, and, following the religious tradition that she grew up with, she called friends and relatives to her room at the Empire Hotel to hear her last words: “How beautiful it is to be with God.”

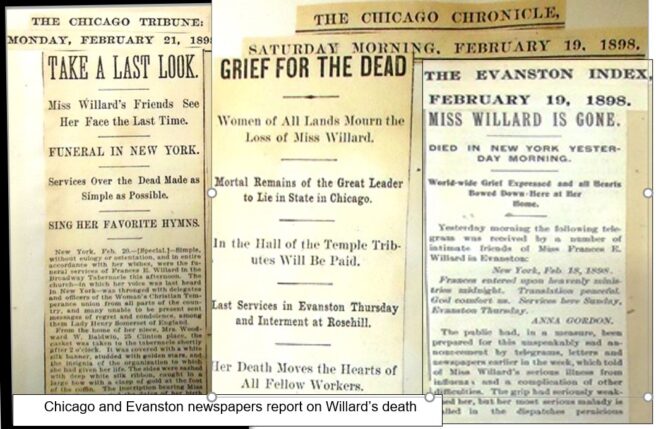

On February 17, 1898, she died.

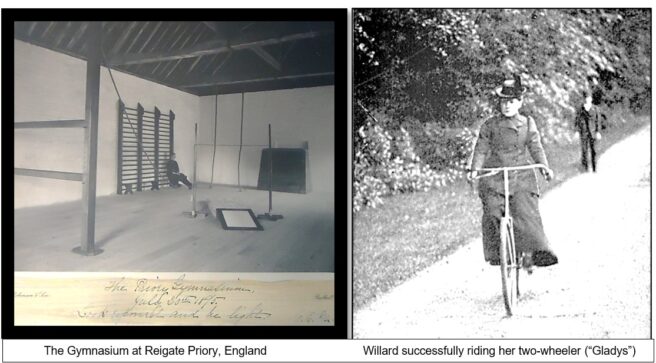

Willard’s body was moved from the Empire Hotel to her niece’s home in New York City. As cablegrams and letters poured in, the first of several funeral services was held in the Broadway Tabernacle. In a location where Willard had previously spoken to crowds, crowds now gathered to pay their final respects.

Willard’s death evoked a popular response similar in many ways to that surrounding Abraham Lincoln’s death in 1865. As Willard’s casket began its slow journey to Evanston in a special train car, WCTU member Matilda Carse said that “In death our adored leader will be greater even than in life. I do not think that the train which brought the body of Abraham Lincoln to Illinois will meet in its progress greater expressions of sorrow than those which will be called for by the sight of the car in which will rest all that is now mortal of Frances E. Willard. The turning of those wheels and the puff of that engine will band a million hearts together in a common pang of sorrow.”

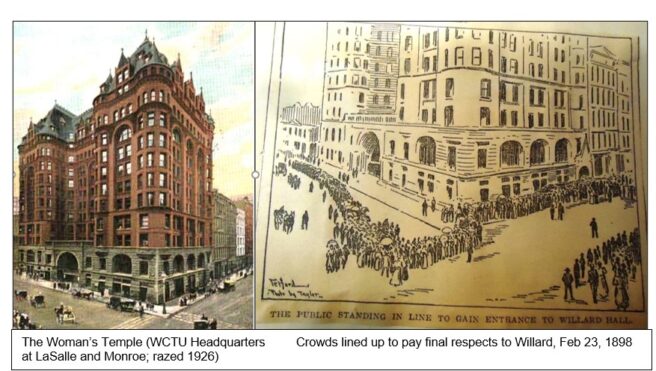

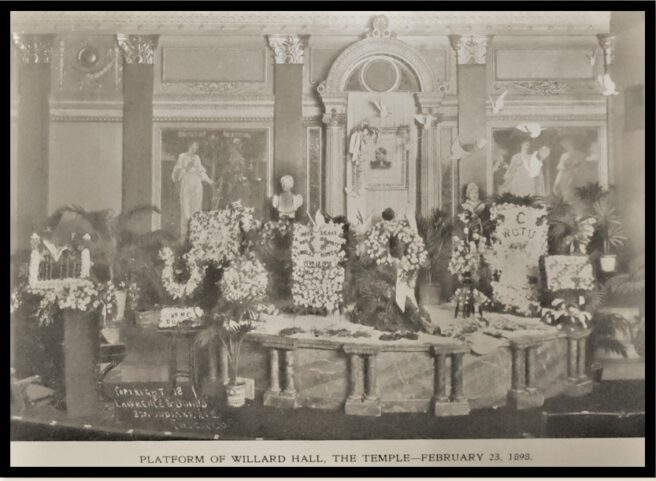

The funeral train stopped first at Churchville, NY, Willard’s birthplace, and then at Buffalo, where she had given her last Presidential address to the WCTU convention in 1897. The train arrived at Chicago on February 23. As the city’s flag flew at half-mast, WCTU members accompanied the coffin to the Woman’s Temple, the WCTU headquarters building, at LaSalle and Monroe. Crowds—one estimate was 16,000—lined up to pay their respects. The casket lay in state for some six hours, surrounded by white draperies, white ribbons (the symbol of the WCTU), and live white doves.

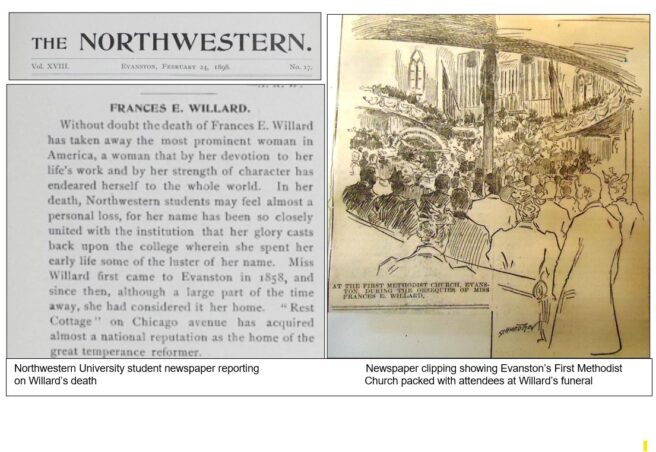

The casket next went by train to Evanston, where hundreds gathered at the Davis Street railway station. Northwestern University students escorted the casket to the Willard family home, Rest Cottage (now the Frances Willard House Museum). On February 24, a memorial service was held at First Methodist, the Willard family’s church since 1858. Northwestern University president Henry W. Rogers was the first speaker, praising Willard’s contribution to the University as dean, teacher, and trustee.

Radical to the last, Willard had made an unusual and– to many traditional Protestants–questionable, request: that she be cremated. Her secretary Anna Gordon was horrified, but finally agreed. Still, Gordon felt obligated to explain the decision, the process, and the actual event in a mass mailing to WCTU members, emphasizing the cleanliness and speed of the procedure, which would turn the WCTU leader’s body into pure white ash, like the white ribbons they all wore. Because Willard had requested that her burial take place in the spring, the body was stored in a vault at Rosehill Cemetery on the far north side of Chicago, where Willard would be buried.

At the time, the only official crematorium in Chicago was a few miles south of Rosehill, at Graceland Cemetery. Willard was cremated there on April 9, 1898. On Easter Sunday, April 10, her ashes were buried at Rosehill, in her mother’s grave, among the plots of other “old Evanstonians.”

Memorials continued long afterward, including biographies, compilations of her sayings, and the naming of children and buildings in her honor. Seven years after her death, on February 17, 1905, a statue of Willard was installed in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol. She was the first woman to be honored with a statue there. Fittingly, sculptor Helen Farnsworth Mears depicted Willard standing at a podium, speech in hand. On the base of the statue appear the “last words” which best reflect Willard’s legacy of empowerment, quoted from one of her early speeches demanding that women gain the right to vote: “I charge you give them power.”

For more information and citations relating to any of the images, documents, and quotations above, please contact archives@cwhlevanston.org.