Elisabeth Heissner is a rising senior at Loyola University of Chicago. Her spring internship with the Frances Willard House Museum & WCTU Archives focused on creating a digital exhibit about the history of WCTU drinking fountains. You can explore the exhibit she created here.

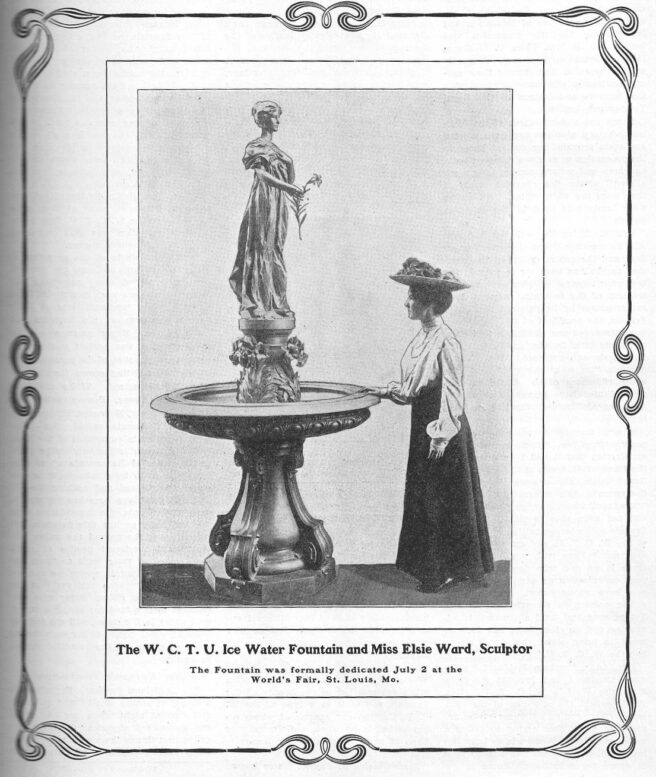

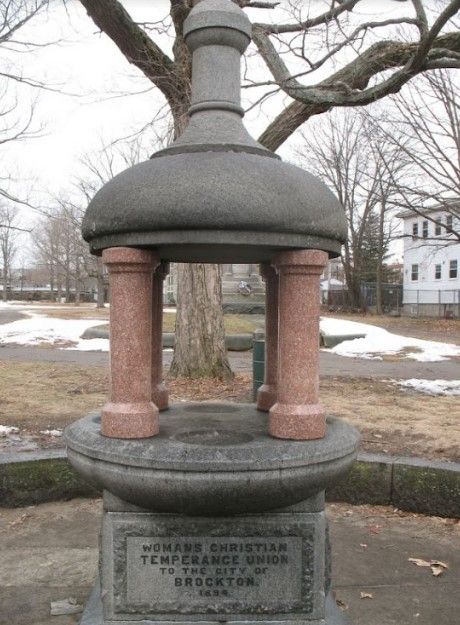

During the month of May, Preservation Month, communities around the country are celebrating historic places and their heritage. In 2022, the theme for Preservation Month is People Saving Places. This theme is especially fitting for the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) due to the large number of WCTU drinking fountains that have been saved through local preservation efforts. Scattered throughout the United States—and even abroad—temperance fountains donated and erected by local WCTU chapters are a legacy of the efforts and influence of WCTU members. Many fountains have been dismantled or lost, but many still remain, often hidden in plain sight, in towns and cities across the country. Restoration projects have brought a number of the fountains back to life.

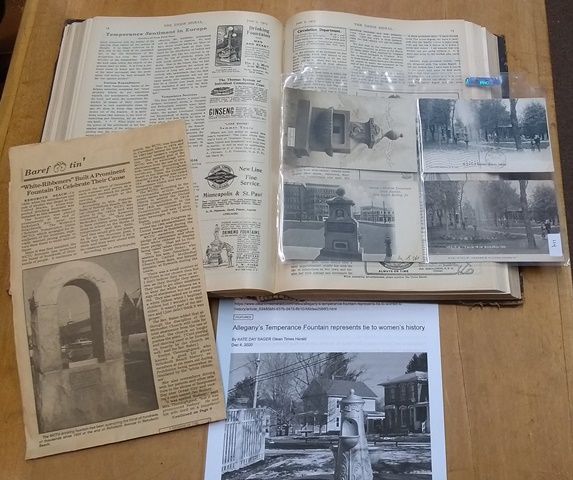

This semester, I set out with the goal of gaining experience with a collection in both an archives and a museum. Fortunately, I was able to nurture both of these interests with my internship at the Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU Archives. Tasked with the project of creating a digital exhibit about WCTU temperance fountains, I used the previous work of former WCTU president Sarah Ward, and did additional research in both the WCTU archives and online resources, to create this project.

Over the course of the semester, I kept a weekly blog of the work that I was conducting and my reflections on the project. One of my biggest takeaways from this assignment was the diligence and consistent research that are required to create a digital exhibit. In a timeline of my assignment, I spent the first month and a half organizing materials. Sarah Ward’s thoroughly researched 80-page booklet, published in 2007, formed the basis of the exhibit. I created a spreadsheet using the information and photographs in her book, and then used the resources of the archives, plus the magic of the internet, to flesh out details. The latter half of my project was spent creating the digital exhibit, which, relative to the research, was much faster. Using the Omeka exhibit platform, I set up pages for each state in the U.S. where fountains had been identified, and plugged in the text and images from the spreadsheet. I also added a map to each state page, showing where fountains in that state were located.

After filtering through all of the dates and pictures of temperance fountains, my favorite aspect of this exhibit is all of the fountains in Massachusetts. Born and raised in the New England state, I had no idea that some of these fountains were this close to my hometown. For example, the temperance fountain in Brockton, Massachusetts is only about a thirty minute drive from my old stomping grounds. I had a similar reaction to my discovery that a temperance fountain is located in Lincoln Park in Chicago, which is only about three miles from my college apartment. Upon finding the “Little Cold Water Girl,” I immediately decided that I would take a trip to Lincoln Park and see this fountain. Given that the design of this fountain was used for many other fountains, the prospect of seeing this fountain was all the more exciting.

I hope that this new online exhibit helps bring a greater awareness to the little historical sites that could be hiding in your town too! There is something really thrilling about realizing how close you may be to a living artifact of history; it makes history more exciting and ties it back to your own life and your community’s story.