By Amelia Perkins, Philosophy PhD student, Northwestern University

I spent this summer as an intern at the Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU Archives, through Northwestern’s Chicago Humanities Initiative, a program which matches graduate students with Chicago-area organizations seeking summer interns. I applied to CHI with the vague idea that it would be good to get some workplace experience outside of the academy; I did not imagine that I would end up with a project I was proud to be a part of, nor that I would still be thinking about it, and working on it, long after my internship officially ended.

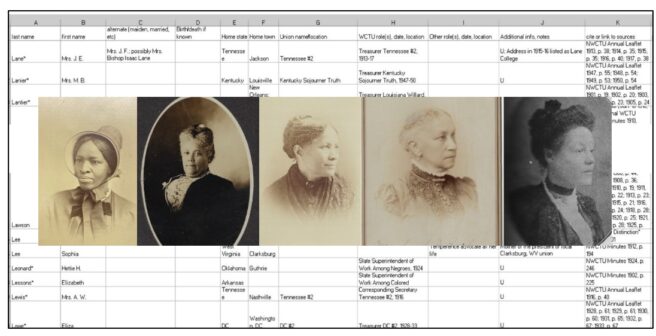

I was brought on to work on the Black Women in the WCTU project, which aims to document the lives and work of the many Black women in the WCTU (Woman’s Christian Temperance Union) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. My main task was the first thing we’d need to do to get the project off the ground: scouring WCTU sources for the names of Black women who participated in the WCTU as National leaders, state-level union administrators, or local-level union officers.

This was trickier than I expected. While Black unions did exist, at the state and local levels, starting in the late 1880s, I first had to learn the naming conventions by which they were distinguished from white and integrated unions. As I found out, at the state level, Black unions often appended “No. 2” to their names (e.g., Maryland No. 2); some state or local unions added the names of famous Black or white WCTU women (there were a number of Thurman Unions, named for Black activist Lucy Thurman, and numerous Frances Willard Unions). Starting in 1945, all the state-level Black unions added “Sojourner Truth” to their names, in a coordinated effort. Once I had a handle on which unions to look for, I could consult the National WCTU’s “Annual Leaflets” for lists of the women who served as state officers for these unions. When I exhausted the names in the leaflets, I moved on to the minutes from the NWCTU’s annual convention, where I read the yearly reports from the National Superintendent of “Work Among Colored People” (as the position was called for most of the years I was investigating).

These reports rewarded careful, close reading. Some years there would be very little of interest in a report; but some years the Superintendent would mention Black organizers by name, or list names and membership numbers of all the Black unions in a given state, or mention, in passing, statewide conventions of local Black unions. It was hard to resist the urge to chase after each of these leads. I wanted to go upstairs in the Archive and start digging around in the boxes of state files, to find out more about these statewide conventions, about the local unions and the work they had been doing. At moments like these, when I caught glimpses of what was happening just beyond the boundaries of the annual reports, I felt I truly understood the importance of the work I was doing. Every woman whose name I added to my working spreadsheet had a story, and by writing down her name and any details I could glean about her, I was beginning the process of telling that story.

By the end of the summer, I was able to collect names and information about the WCTU roles of over 500 women, as well as the locations and years of operation of over 25 state and local Black unions. While I’m proud of the progress we made in a few short months—and I loved to exclaim, with my colleagues in the Archives, over how much bigger the spreadsheet was getting each week—it was even more exciting to see the portraits of individual women emerge from the information I collected.

I found family connections, such as the mother-daughter duo of Margaret Peck Hill and Violet Hill Whyte. Hill was first mentioned in a Superintendent’s report as a “wide-awake young organizer” in 1914, and went on to serve as the president of Maryland No. 2 for 29 years. Whyte held a number of state leadership positions too, finally rising to become National Director of Work Among Colored People in 1932. I tracked women as they moved all over the United States organizing (such as Frances Preston, who held leadership roles in both Michigan and Florida during the first two decades of the 20thcentury) and went to Europe for the WCTU (as Elizabeth Fouse did in 1947).

At the beginning of my internship, more than one person asked me whether I was sure I’d find the way I’d signed up to spend my summer interesting. After all, I’m not even a historian; my field is Ancient Greek philosophy. Would it really be exciting for me to find and organize 80 years-worth of names? I understand the incredulity. Just looking at a list of names, it’s hard to get a sense for the people behind them. But in all the activity of putting the list together, in the cross-referencing and cataloguing I did every day at the Archive, I started to see flashes of animation. I started to see the women coming to life.

Amelia Perkins is a doctoral student in Philosophy at Northwestern University. We thank her for her above-and-beyond work on this project, which she has continued after her summer internship ended. Her close reading and insightful suggestions have greatly advanced the work. We also thank Northwestern University and the Chicago Humanities Initiative for choosing us a host institution and matching us with Amelia—a match that was mutually beneficial and fruitful.