By Fiona Maxwell, UChicago Grad Global Impact Intern

In November 1871, the Evanston College for Ladies threw open its parlor for a Thanksgiving “sociable.” The College’s President Frances Willard displayed “pains-taking care” in her preparations in order that all of the guests enjoyed “themselves to the fullest extent.” After the formalities of “introduction and conversation,” the College parlor was transformed into a stage, and “the enacting of charades” furnished the rest of the “amusement of the evening.”

Nineteenth-century Americans of all ages engaged in a variety of dramatic activities, including storytelling, story dramatization, dramatic reading and recitation, parlor games, charades, farces, pantomimes, and tableaux vivants. Drama was part of a larger culture of participatory art. People also entertained themselves, their friends, and their families through instrumental and vocal music, as well as through the visual arts and handicraft. Mass entertainment had not yet absorbed people’s intense devotion to amateur artistic pursuits. This was a world where ordinary Americans were as much cultural producers as consumers, and created a sense of community based on watching, discussing, and participating in performances of literature and music.

In the decades following the Civil War, Evanston was a small but vibrant center of the literary and performing arts. Frances Willard, a pioneering female orator, temperance and woman’s suffrage leader, and the first Dean of Women at Northwestern, described Evanston as “the literary center of the great Northwest.” It housed Northwestern University, Garrett Biblical Institute, and the Cumnock School of Oratory, a separate elocution school that eventually became the Northwestern School of Speech. Young and old alike gathered in homes, literary societies, and church assembly rooms to participate in and listen to “literary and musical entertainments.”

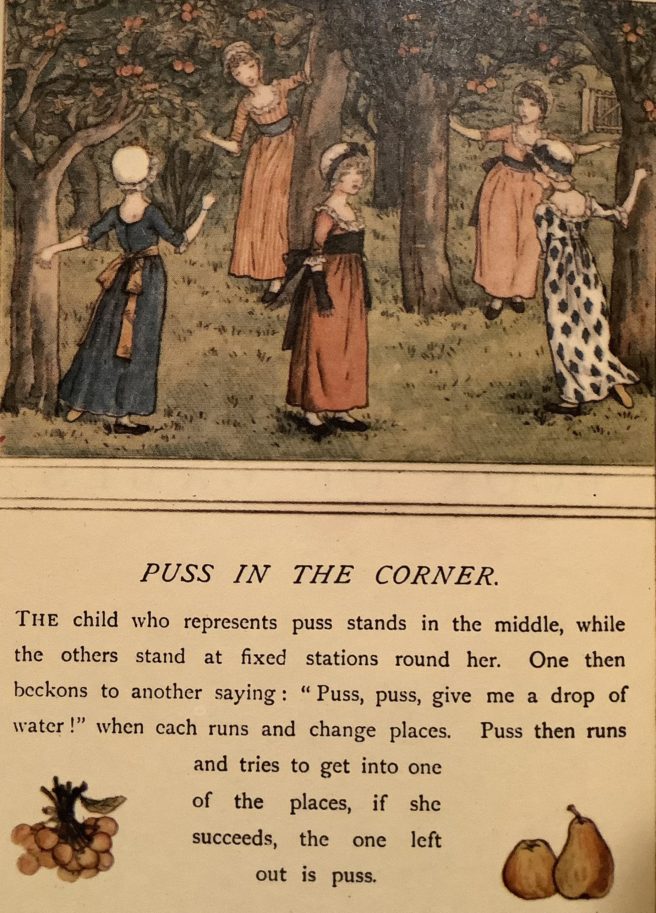

Theatrical parlor games provided a bit of everyday fun. “Blind man’s [bluff], hide and seek, and pussy wants a corner, with an occasional foot race, help to enliven the time between tea and study hours,” reported a resident of the Northwestern Woman’s College. Some games asked players to recite poetry or take on characters from literature. Games could be accompanied by a guest playing the guitar or parlor organ. On holidays, guests played thematic games, made elaborate costumes, and received hand-crafted party favors.

Young women were particularly innovative and resourceful when planning dramatic performances. In 1875, students and townspeople filed into the Northwestern Woman’s College to witness “a fine entertainment… under the management of the ladies of Evanston.” Carrie Kennicott began the program with an “impressive” rendition of “The Meeting between Queen Elizabeth and Mary, Queen of Scots,” accompanied by two tableaux vivants, or living pictures. One of the performers, Stella Burke, “in her Elizabethan costume, almost compelled us to bow the knee, so well did she represent the queen.” The spectators did not remain passive for long, as a “charade, written for the occasion by Mrs. H. M. Kidder, was next given to the audience to develop their guessing powers.”

Many women who studied dramatic reading in Evanston nurtured professional ambitions and found frequent opportunities to perform in public. Robert Cumnock, Northwestern’s elocution instructor and a nationally renowned dramatic reader, trained women to develop their creative and authoritative voice at a time when the very concept of female public speakers was suspect. Frances Willard studied with Cumnock in 1872 and later wrote that compared to the speech instructors of New York, Cincinnati, and Philadelphia, “our own canny Scotsman excelleth them all.” Cumnock trained mostly female students in his School of Oratory, and he established a national network of women performers, professors, and teachers. Women transferred the dramatic abilities they gained from classes, literary societies, and parlors to a variety of professional settings, including platforms, settlement houses, schools, libraries, park districts, and universities. The parlor was a rich site of collaborative and participatory performance, as well as a training ground for women interpretive artists, lecturers, educators, and reformers.

Intern Fiona Maxwell is funded through the University of Chicago’s Grad Global Impact program, which is part of the PATHS, a Mellon Foundation funded project at the University. We are grateful for their support of her work.