By Fiona Maxwell, University of Chicago Graduate Global Impact Intern

This is the first installment of a series of blog posts highlighting a small sample of the printed performance materials housed in the WCTU Archives. Although the Museum and Archives are closed to visitors due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we are committed to providing digital access to our historic site’s unique story and resources. We suggest parents and teachers share these “Performing Temperance” posts with interested young people at a middle school reading level and above. Students and researchers interested in the ways Americans “performed temperance” during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are encouraged to explore our collection once we reopen!

Nineteenth-century Americans participated in activities and events based on reading and speaking over the course of their lives. Children learned to read by reading out loud. Schoolboys and girls as well as college students studied elocution books called “reciters” and performed orations, poems, stories, dialogues, and playlets in public exhibitions. Adults continued their speech education through literary societies and voluntary associations. Oratorical skills were deemed crucial for men seeking careers in law, ministry, and politics. While women were usually expected to perform in semiformal occasions, many ascended the rostrum as academics, reformers, lecturers, and interpretive artists.

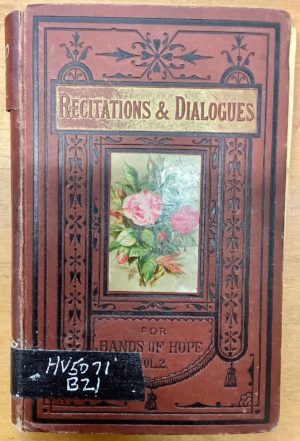

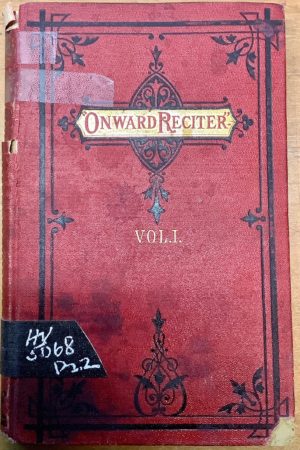

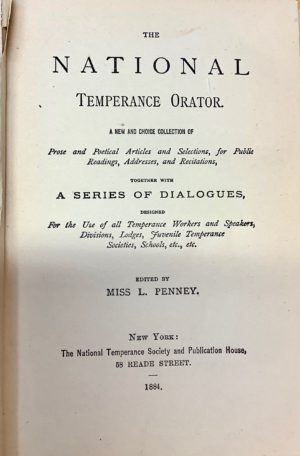

Temperance advocates adapted this common pedagogical technique to further their reform agenda. The WCTU Archives possess many nineteenth-century temperance reciters. Some, such as Recitations and Dialogues for Bands of Hope and The Onward Reciter (1872),were published in England for use by the Band of Hope Union. Others, including The Temperance Speaker (1874; 1884), The National Temperance Orator (1884), and The National Temperance Platform (1896), were published by the New York-based National Temperance Society and Publication House. Many selections were written by women, addressed women’s specific concerns, and were performed in all-female settings like WCTU meetings. Some collections were aimed at child readers or listeners, while others were intended for adult performers and audiences.

Educating children was an essential part of temperance activism. Reformers believed that it was easier to prevent children from becoming addicted to alcohol than it was to “reclaim the fallen.” To achieve their educational goals, temperance advocates established youth groups for boys and girls, including the Band of Hope, the Loyal Temperance Legion (under the auspices of the WCTU), and the Young Abstainer’s Union. Spoken performance was a key aspect of the curricula of temperance youth groups and Sunday schools. Growing demand for “attractive and suitable recitations” led reformers to compile collections of temperance poetry, prose, dialogues, and debates for children to perform. Editors also inserted general works by the “best” authors in an effort to introduce children to selections they believed possessed literary merit. These collections feature pieces by canonical and popular authors, as well as social reformers, orators, religious leaders, politicians, and amateur writers.

Many WCTU members became poets, short story writers, novelists, and playwrights in order to supply “wholesome” literature for child readers and audiences. Additionally, temperance women were the largest group of female orators in nineteenth-century America. The WCTU provided many women with their first and only chance to speak in public and offered a space where they could learn this new skill in the company of other women. National WCTU President Frances Willard advised members to overcome their discomfort and inhibition concerning speaking by performing as often as possible in public meetings and at conventions. The WCTU established a lecture bureau which arranged tours for female temperance speakers. Women used temperance speeches to discuss woman’s suffrage and other issues that concerned women and children. WCTU members consulted “reciters” to practice public speaking and to choose selections for performance.

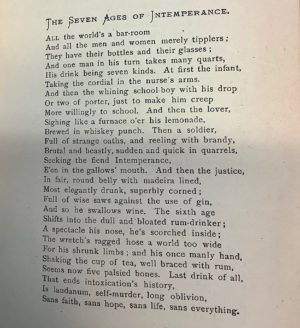

The National Temperance Orator is a representative temperance reciter. It is one of many compiled by Lizzie Penney for the National Temperance Society. The collection contains prose, poetry, and dialogues for performers of both genders and all ages. Its recitations imply that it was never too early for children to take the temperance pledge. In “The Little Boy’s Song,” a toddler sings: “I am a temperance boy / Just four years old, / And I love temperance / Better than gold.” Alongside pieces for young people were political orations for adults, including “Indictment of the Traffic,” “Intemperance the Great Social Battle of the Age,” “Make it a Political Question,” and “Prohibition.” The collection even satirizes Shakespeare. “The Seven Ages of Intemperance” parodies “The Seven Ages of Man,” the famous “All the world’s a stage” monologue from As You Like It, by relating every line to drinking: “All the world’s a bar-room / And all the men and women merely tipplers.” Contributors include WCTU members Julia Colman and Nellie Bradley, professional women writers and reformers, and male temperance activists, religious leaders, doctors, politicians, professors, and orators.

WCTU members believed that speaking was more effective than print for promoting the causes they believed in. “The leaflet,” they argued, “cannot substitute, and should not supplant, the lecture.” Yet, both men and women temperance advocates relied on printed reciters to educate children and hone their speaking skills.