By Fiona Maxwell, University of Chicago Graduate Global Impact Intern

This is the second installment of a series of blog posts highlighting a small sample of the printed performance materials housed in the WCTU Archives. Although the Museum and Archives are closed to visitors due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we are committed to providing digital access to our historic site’s unique story and resources. We suggest parents and teachers share these “Performing Temperance” posts with interested young people at a middle school reading level and above. Students and researchers interested in the ways Americans “performed temperance” during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are encouraged to explore our collection once we reopen!

For Americans growing up in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, competing in a public speaking contest was a key part of educational life. Students from elementary school through college were ushered into assembly rooms, churches, and theaters to display their elocution skills. A lucky few carried off medals or money. Girls and women fought to participate in coeducational oratorical contests. While some won the chance to recite, only a rare female contestant managed to win over the male judges who were used to awarding prizes to men declaiming “Horatius at the Bridge” and “Daniel Webster’s Speech to the Senate.” When a girl or woman did win, she often endured ridicule and condemnation in the student press. She could even have her victory called into question or revoked.

Having participated in school speaking contests, temperance women recognized that contests were both useful educational tools and highly public events. The WCTU established a system of oratorical contests run by women, for women and children. They made sure that their contests offered a space where women and girls could develop speaking skills and carry off the laurels of victory. Oratorical contests were one of many ways that the WCTU promoted women’s public speaking and drew attention to their reform agenda through oratory.

William Jennings Demorest, a New York magazine publisher, philanthropist, and supporter of temperance and woman’s suffrage, established the Demorest Medal Contest in 1886 in collaboration with the WCTU “to train children and young people to recite or declaim the Temperance orations of leading speakers.” By 1895, these contests had awarded over 40,000 medals. Contest managers claimed that 250,000 children had participated, and that their events had reached a total audience of over fifteen million people. WCTU speaking contests even appeared in fictional literature – in Emily of New Moon by L. M. Montgomery, the author of Anne of Green Gables, budding elocutionist Ilse Burnley wins a medal in a recitation contest sponsored by the Charlottetown WCTU. Frances Willard believed that oratorical contests educated both the young participants and their adult listeners: “By means of these contests, which always draw large audiences, a strong influence is exercised on the public mind which results in better habits and better testimony at the ballot box.”

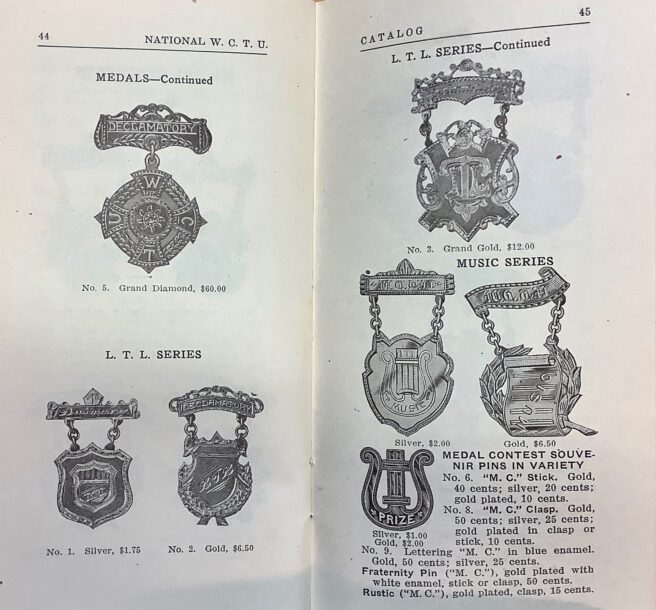

WCTU oratorical contests for women and children continued throughout the twentieth century. Contests were arranged by local judges, following rules set by the National WCTU. Contestants chose selections from WCTU booklets, Demorest’s Speakers, or the WCTU’s many collections of stories and poems for child contestants, which were graded by age group and contest level. Medals could be won for a variety of contests, including “Demorest, Suffrage, L. T. L. [Loyal Temperance Legion], Mercy or anti-narcotic.” In the years surrounding WWI, contests dedicated to “Peace and Arbitration” and “Patriotism” were added.

The WCTU Archives contain over fifty different oratorical contest booklets that provide insight into what contestants recited and how they prepared. The booklets were compiled by Adelia Carman, the National WCTU Superintendent of Medal Contests, and were printed at the WCTU’s National Headquarters, located in the Woman’s Temple building in Chicago. They contain orations by authors, reformers, religious leaders, and politicians. The pages are peppered with advertisements for schools of oratory in Chicago, as well as elocution correspondence courses run by women from small Illinois towns. The WCTU officially endorsed the Columbia College of Expression and Physical Culture, a school of oratory found by WCTU member Mary A. Blood. “Elocution lessons by mail” required a student to send her selection to the instructor, who provided written guidance concerning vocal expression and gesture. These ads encouraged women to not only vie for WCTU medals, but to develop professional speaking skills.

What did victorious women and children receive for their efforts? The National WCTU catalogs featured medals that could be ordered by local unions and distributed to winners. Medals came in silver, gold, grand gold, first diamond, and grand diamond. There was a Loyal Temperance Legion series for children and a Matron’s series for older women. Medals ranged in price from $1.75 for silver to $60.00 for grand diamond, which is worth approximately $23 and $776 in 2020 dollars – expensive prizes for locally sponsored contests. The WCTU Archives contain a display case of WCTU oratory medals, some of which date from the 1890s.

For thousands of women and children, participating in a WCTU contest was their first experience speaking in front of a public audience. Memorizing and reciting an oration, story, or poem taught contestants valuable performance skills that they could later put to use in a variety of educational and professional settings. As community events that often drew hundreds of spectators, the WCTU not only used contests to encourage women to speak in public; they also used them to teach audiences to take female speakers seriously.