By Fiona Maxwell, University of Chicago Graduate Global Impact Intern

This is the third installment of a series of blog posts highlighting a small sample of the printed performance materials housed in the WCTU Archives. Although the Museum and Archives are closed to visitors due to the COVID-19 pandemic, we are committed to providing digital access to our historic site’s unique story and resources. We suggest parents and teachers share these “Performing Temperance” posts with interested young people at a middle school reading level and above. Students and researchers interested in the ways Americans “performed temperance” during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries are encouraged to explore our collection once we reopen!

Early twentieth-century Evanston was the epicenter of two movements – temperance and children’s drama. Just down the street from Frances Willard’s home and the WCTU National Headquarters was the Northwestern University School of Speech, where theater educator Winifred Ward developed her Creative Drama methodology. In fact, Ward had studied elocution with Northwestern professor Robert Cumnock, the same man who had trained Frances Willard in public speaking during the 1870s. Children’s drama merged with women’s activism as the WCTU printed and staged plays, skits, and pageants for amateur and educational settings, some of which used aspects of Ward’s approach.

The WCTU Archives feature 260 scripts written, published, and produced by WCTU members. They address a variety of reform topics, including temperance, woman’s suffrage, child welfare, peace, health, and social service. The following four examples offer a glimpse into the WCTU Archives’ rich collection of children’s dramatic materials.

Many plays combined pageantry and politics. Anna Gordon, Frances Willard’s personal secretary and the fourth president of the WCTU, authored countless stories, poems, and songs for children. Gordon wrote The Children’s Tribute to the Prohibition States: A Prohibition Playlet sometime after the failed attempt at national prohibition legislation in 1915 and before the ratification of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1919. In the playlet, she celebrated states that had passed statewide dry laws. “Nineteen young ladies of uniform height dressed in white represent the prohibition states,” a dramatic reader provides narration, and a child presents each state with “a wreath of laurel or green leaves.”

Drama was also used to teach the history of the temperance movement. The Crusade Story: A Pageant is a dramatization of the Woman’s Crusade by Mrs. W. P. Chase, who adapted a chapter from Elizabeth Putnam Gordon’s Women Torch-Bearers: The Story of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (1924). The Woman’s Crusade was a series of nonviolent protests during the winter of 1873-1874, in which women gathered outside of saloons, prayed, sang, and demanded that saloonkeepers stop selling liquor and find a new line of business. Following crusades in 900 different communities, located in more than thirty-one states, women crusaders formed the WCTU. Through The Crusade Story, the WCTU instructed members and younger generations about their origins and celebrated women’s moral influence, piety, and public activism.

Many materials dramatize the life and work of Frances Willard, who had become a legendary figure after her death in 1898. The Uncrowned Queen: Dramatic Monolog in Seven Incidents based on the life of Frances E. Willard was advertised to local WCTUs, Woman’s Clubs, Parent Teacher Associations, churches, and other groups in 1939 – the one hundredth anniversary of Willard’s birth. Written by Jane Good, the piece was published by the Creative Dramatics Department of the Northwestern School of Speech and drew on elocution and storytelling methods. Good hoped that her “dramatic monolog… will be presented by a talented young woman in many localities before clubs and groups of various kinds. Thus the general public may come to know better, in this, her centenary year, that great humanitarian, Frances E. Willard.”

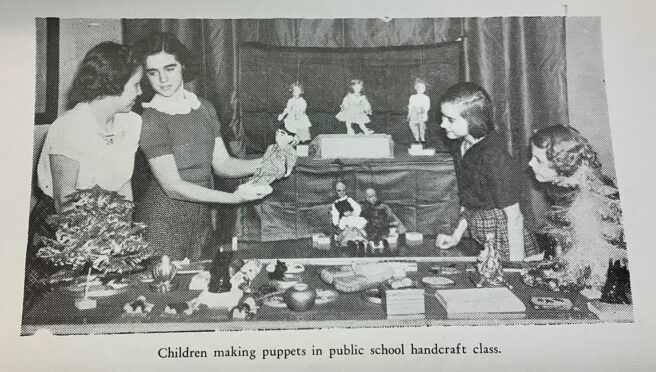

During the mid-twentieth century, puppetry became increasingly popular in children’s drama circles. Helen Elliott crafted a do-it-yourself manual for enacting Frances Willard’s early life with puppets, titled Born to Lead: A Puppet Play, The Childhood of Frances E. Willard. Elliott included a list of books, periodicals, and booklets containing instructions for amateurs seeking to make puppets and put on shows. To create “costumes of the period,” readers were directed to Genevieve Foster’s illustrations in Pioneer Girl: The Early Life of Frances Willard (1939) by Clara Ingram Judson. Elliott intended the play for child audiences “of a wide age-range.” She was confident that “the play will hold the children’s interest” and “they will absorb every word.”

Nineteenth-century WCTU members had embraced oratory and dramatic reading as tools to promote their agenda, educate children, and train women public speakers. By the 1910s and 1920s, solo dramatic reading was gradually giving way to play production, and elocution was beginning to be replaced by theatrical training. The WCTU identified plays for young performers and audiences as a new and modern way to “perform temperance” and to further their reform and educational goals.