Part 2 of a series

By Janet Olson, CWHL archivist.

During 2024, to mark the 150th anniversary of the founding of the National Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (November, 1874), we will be shining a local spotlight on the Evanston women (and men) who were “early adopters” of the temperance campaign. This joint project of the Evanston Women’s History Project and the Center for Women’s History and Leadership draws upon the many historical resources available in Evanston to address the rhetorical question that WCTU member Jennette Hauser posed in 1883: “What is the use of a temperance society in Evanston, where the sale of liquor is already prohibited?”

As you may recall, the Woman’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston first met on March 17, 1874 [1] at Union Hall to make plans for ensuring that all of Evanston supported temperance work and could serve as a shining example to less enlightened municipalities.[2] By April, the Alliance had met several times, and Elizabeth Eunice Smith Marcy—Mrs. Dr. Marcy—had been elected president. Marcy (1821-1911) was well qualified for the position. She represented both town and gown: her husband, Oliver Marcy, was the interim president of Northwestern University, and Elizabeth was very much involved with Evanston’s First Methodist Church, for which she helped raise money for the construction of the church’s second building in the early 1870s. Although the bulk of her philanthropic work occurred after the mid-1870s, her participation in the Evanston and national temperance movements may have inspired her later activism.[3]

The April 4 issue of the News-Index reported on a recent meeting of the Alliance, where “interesting remarks were made by a number of our own ladies and ladies from Indianapolis.” The main focus of the meeting, however, was to implement the plan discussed earlier to “pledge the town”–a term they may have originated–to ensure that every Evanstonian had signed a form pledging to abstain from alcohol. At the meeting, the town was divided up into districts, and Alliance members were asked to visit residents and business owners in each district to sign the temperance pledge. The meeting concluded with a call for volunteers to give the pledge “a thorough circulation so that every person in Evanston may have a chance to sign.”[4] Volunteers could sign up with Mrs. Marcy or with the organization’s secretary, another town/gown Evanstonian, Anna Green Fisk–“Mrs. Prof Fisk–” the wife of Northwestern preparatory school principal Herbert Fisk.

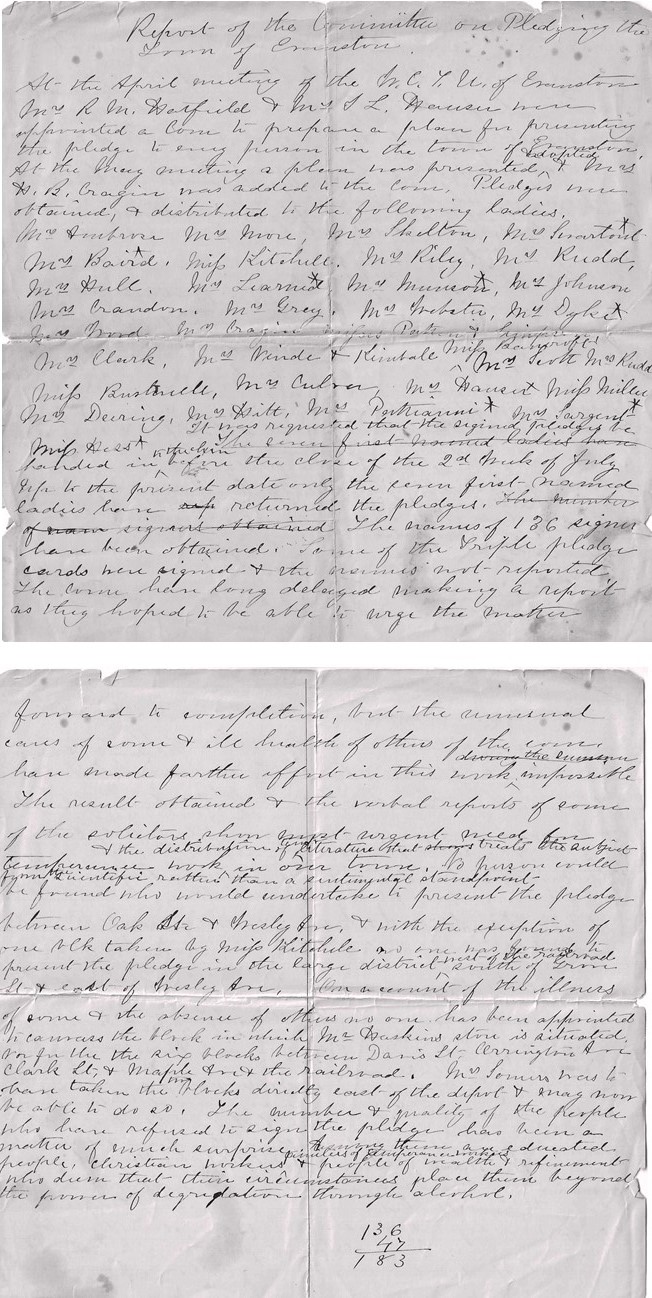

According to a later handwritten Report of the Committee on Pledging the Town of Evanston, submitted sometime in the summer or fall of 1874, pledge cards were “distributed to the following ladies” in April:

Mrs. Ambrose, Mrs. More, Mrs. Skelton, Mrs. Swartout, Mrs Baird, Miss Kitchell [?], Mrs Riley, Mrs Rudd, Mrs Hull, Mrs Learned [?], Mrs Munson, Mrs Johnson, Mrs Crandon, Mrs Grey, Mrs Webster, Mrs Dyke, Mrs Wood, Mrs Cragin, Misses Parker [?] & Springer [?], Mrs Clark, Mrs Ward [?] Kimball, Miss Bancroft, Mrs Scott, Mrs Rudd, Miss Bushnell, Mrs Culver, Mrs Hauser, Miss Miller, Mrs Deering, Mrs Hitt, Mrs Perthianni [?] Mrs Sargent, Miss Hess.[5]

As this list suggests, the story of the Woman’s Temperance Alliance reads like a directory of the women of early Evanston. Their network was connected by their work in the various Protestant churches, their husbands’ occupations (at the University, in town, or in Chicago), their children’s schools and playmates, and the local businesses they frequented. Together, they were a force intent on protecting their families and setting an example.

The Committee’s report showed that the effort to pledge the town had run into delays typical of many ambitious schemes. “Up to the present date [unknown] only the seven first-named ladies have returned the pledges. … [and] the unusual cares of some & ill health of others of the com[mittee] have made farther effort in this work impossible.” For several of the districts, no volunteer had come forward. In addition, the canvass revealed that:

The number & quality of the people who have refused to sign the pledge has been a matter of much surprise. Among these are educated people, Christian workers… & people of wealth & refinement who deem that their circumstances place them beyond the powers of degradation through alcohol.

Nevertheless, the report stated, 183 pledges had been collected so far, and the signers’ names added to the lengthening list in the organization’s minute book—itself a virtual directory of Evanston residents—men, women, and children.

But the public campaign to prove by pledges that Evanston was proudly dry was not the only goal of the Woman’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston. At the original meeting, the women had also vowed to enforce the laws governing behavior in the town: they well knew that, despite their best efforts, the “University Charter law” establishing a four-mile alcohol-free limit continued to be flouted by townspeople clandestinely selling liquor and, what’s more, maintaining gambling and smoking establishments.

The progress of the Alliance and their stalwart allies as they continued the crusade to track down and prosecute these offenders, will be addressed in the next installment of this blog series, along with more on the results of the efforts to “Pledge the town.”

[1] See blog post #1, March 24, 2024, describing the motivation behind the organization’s founding.

[2] Union Hall was built by attorney Andrew Brown (1820-1906)—one of the founders of Northwestern, and longtime Evanston resident—on what was then the 200 block of Davis Street, opposite the Evanston News Index office. The Hall opened in early March, 1874, just in time to host the first meeting of the Woman’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston. The women continued to hold many of their meetings at Union Hall. Brown’s wife, Abby McCagg Brown, was involved in women’s education in Evanston, as well as in the temperance movement and in her church.

[3] The Marcys moved to Evanston in 1862. Their house was on the northeast corner of Church and Chicago, the block known as old-timers’ row from its association with early Evanston residents. (The Willard family lived a few houses north on the opposite side of Chicago Ave.) See “Letter to the Editor,” Evanston Index, September 13, 1888, for the use of the term “old timer’s row” for the 1700 block of Chicago Avenue. (Thanks to Mary McWilliams for this bit of information.) Elizabeth Marcy’s philanthropic work took shape in the mid-1870s, after one daughter died and the other married. Marcy was fully engaged with the early WCTU; she then became very involved in the Methodist Woman’s Home and Foreign Missionary Societies, and in the 1890s helped found the Elizabeth Marcy Settlement House in Chicago (see https://findingaids.library.northwestern.edu/agents/people/2100)

[4] “The Woman’s Temperance Alliance,” Evanston Index, April 4, 1874, p. 3

[5] This list of names and the two following quotations come from “Report of the Committee on Pledging the Town of Evanston,” [no author, no date] ,” Box 1, folder 4, Records of the Evanston WCTU, 1874-1992, WCTU Archives. The handwritten document is pictured here. (Transcribed by Janet Olson. Help deciphering the names marked with ? would be appreciated.) More information about many of these women can be found on the Evanston Women’s History Project research database and/or in the research files at the Evanston History Center.