By the Staff of the Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU Archives

In the August 29, 2023 issue of Chicago Magazine, Edward Robert McClelland advocated, somewhat lightheartedly, for replacing the statue of Frances Willard in National Statuary Hall with a figure that would better represent “modern Illinois.” While the two women he suggests as replacements – poet Gwendolyn Brooks and Hull-House founder Jane Addams – would make excellent companions to Willard as representatives of Illinois women, we maintain that Willard’s continued significance in our times justifies her statue’s enduring location in our nation’s Capitol building.

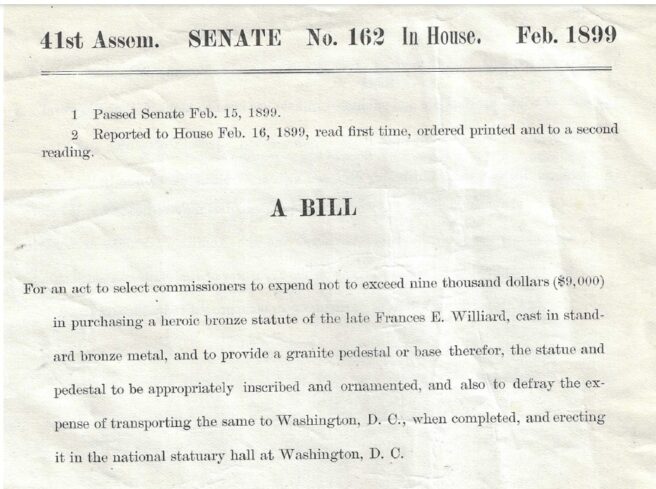

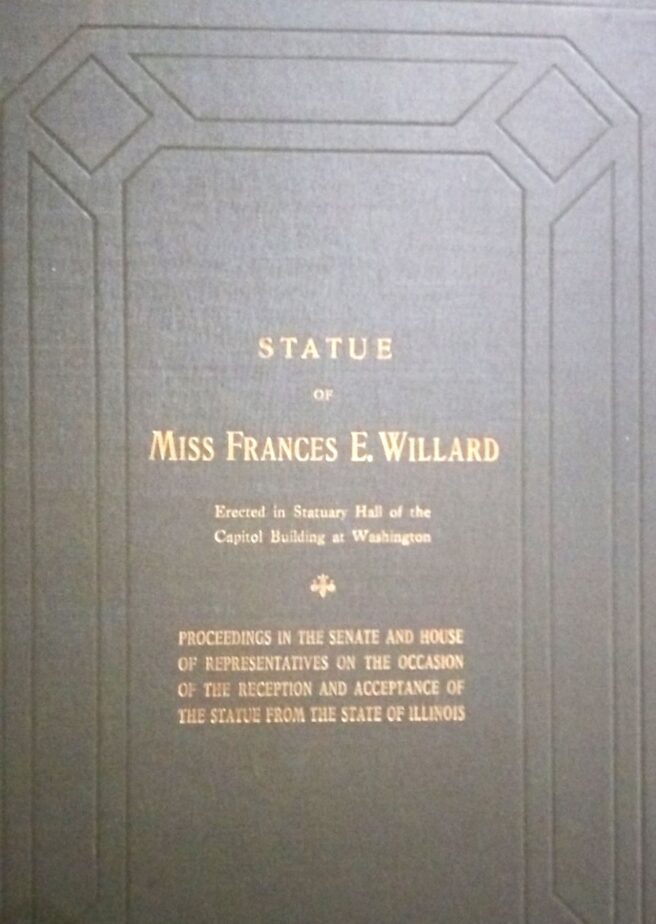

Let’s begin with the dedication of Willard’s statue. On February 17, 1905 – exactly seven years after her death in 1898 – Frances Willard became the first woman memorialized in National Statuary Hall. In his dedication speech, Shelby Moore Cullom, U.S. Senator from Illinois,[1] noted that since twenty states had thus far presented representations of its two most “distinguished men,” Illinois broke precedent when it “selected a woman thus so signally to honor.” Furthermore, the acceptance of Willard’s statue marked “the first time in the history of the Senate a day has been set apart that we may talk of a woman.”

Cullom’s speech (published, among other speeches delivered on that occasion, in a commemorative book by the Government Printing Office) attested to Willard’s continued importance even after her death. In reviewing Willard’s “wonderful career” Cullom described her student days in Evanston, her early career as an educator, and her tenure as Northwestern University’s first Dean of Women. He then spoke of her twenty-year presidency of the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) – the largest women’s organization in the country at the time – where “her splendid executive ability” transformed the new organization into a global movement. Her “Do Everything” agenda encompassed not only temperance, “but all other beneficial, progressive reforms,” including “purity in politics” and “equal rights for women.” When she died, “the world stopped to mourn.” Cullom affirmed that, by placing the statue of Willard “among the figures of the greatest men that have lived in the United States,” Illinois had “justly honored a great woman.”

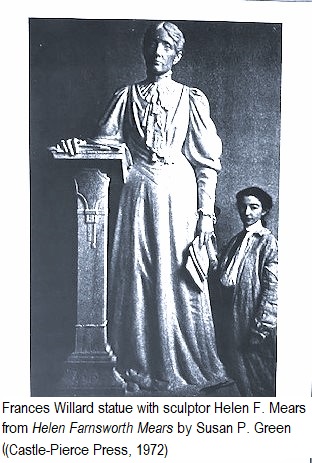

The design of Willard’s statue further validates its long-lasting value as public art. Susan B. Anthony had stressed that Willard’s sculptor must be a woman,[2] and the commission was given to noted artist Helen Farnsworth Mears, who had studied and worked with sculptors Augustus Saint Gaudens and Lorado Taft.[3] Mears sculpted a compelling image of Willard standing at a lectern, directly meeting the gaze of her audience as she delivers a speech, notes clasped in her hand. This bold stance carried symbolic meaning. For women of Willard’s generation, engaging in public oratory was a radical act. Since the 1820s, women had been counseled to avoid speaking before large, mixed-sex audiences. Those who did were instructed to keep their eyes lowered and to speak from a prewritten text. Willard discarded these rules early in her speaking career, and went on to inspire thousands of new women orators inside and beyond the WCTU to vocally advocate for change and to demonstrate their political competency.

Finally, the text carved on the plaque under the statue quotes one of Willard’s earliest and most powerful speeches,[4] used here as a mandate to the statesmen who would view the statue every day: “I charge you give them [women] power.” Willard – and Mears – thus expressed their vision of women achieving the right to vote, a vision that Willard did not live to see, although she empowered a generation of women to make it happen.

The author of the Chicago Magazine article quipped that few present-day Illinoisians know Frances Willard’s name or want to take a selfie with her, but this is not a sign that she should be evicted from Statuary Hall. Nor is the nineteenth century a collection of “deadwood” that needs to be “cleared out” wholesale. While history requires constant reassessment (as a museum and archives, we are continually engaged in reexamining Willard’s legacy), in this case Willard’s alleged obscurity presents an opportunity to uncover essential insight into how women fought – and continue to fight – for equal access to political participation.

Regardless of whether the citizens of Illinois decide that Willard is still their ideal representative in Statuary Hall, her statue deserves further contextualization, not expulsion. We can take pride in the fact that Illinois had the foresight and courage to install a monument to a woman in the male domain of Statuary Hall. Given that American women still struggle to be treated as serious political figures – and that their public voices are still dismissed – the historic image of this Illinois woman delivering a speech in the United States Capitol remains as meaningful as ever.

The WCTU Archives hold much information about the statue, including documents, correspondence, and newspaper clippings. Holdings also include the commemorative medals given to children who attended the dedication ceremony in 1905.

[1] Cullom was Illinois’ longest serving senator and a former governor. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shelby_M._Cullom

[2] Our files include a letter from Anthony stating that the sculptor of Willard’s statue “certainly” needed to be a woman since men did not know how to show strength of character in a woman without giving her a masculine look. (Frances Willard Papers, Box 22, folder 22, WCTU Archives.)

[3] For more about Mears, see Helen Farnsworth Mears, by Susan Porter Green (WI, Castle-Pierce Press, 1972), or https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Helen_Farnsworth_Mears. When her mentor St. Gaudens saw Mears’ statue, he said: “Only a woman could have made the statue of Miss Willard. It is as a strong as a man’s work, and has in addition a subtle, tangible quality exceedingly rare and spiritual.”

[4] The quote is taken from the last paragraph of Willard’s first “Home Protection” speech, delivered in 1876. For more about the speech, see Let Something Good Be Said: Speeches and Writings of Frances E. Willard (edited by Carolyn DeSwarte Gifford and Amy R. Slagell; University of Illinois Press, 2007), pp. 17-25. The entire speech is also online at https://speakingwhilefemale.co/temperance-willard7/