One hundred years ago today, May 20, 1922, the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union Administration Building opened, signaling a full and final shift of the organization’s headquarters to Evanston. Located directly behind the Willard House at 1730 Chicago Avenue, this significant building hides in plain sight. Though no longer functioning as the WCTU’s national headquarters building, it continues to house the WCTU Archives and Research Library. And, like the Willard House, it is on the National Register of Historic Places. Together, the House and the Administration Building tell important stories about women’s history in the U.S. But the house, where Frances Willard lived from 1865 to 1898, is better known. The following excerpts from Museum Director Lori Osborne’s 2001 nomination of the Administration Building to the National Register outline the history of the building on its 100th birthday.

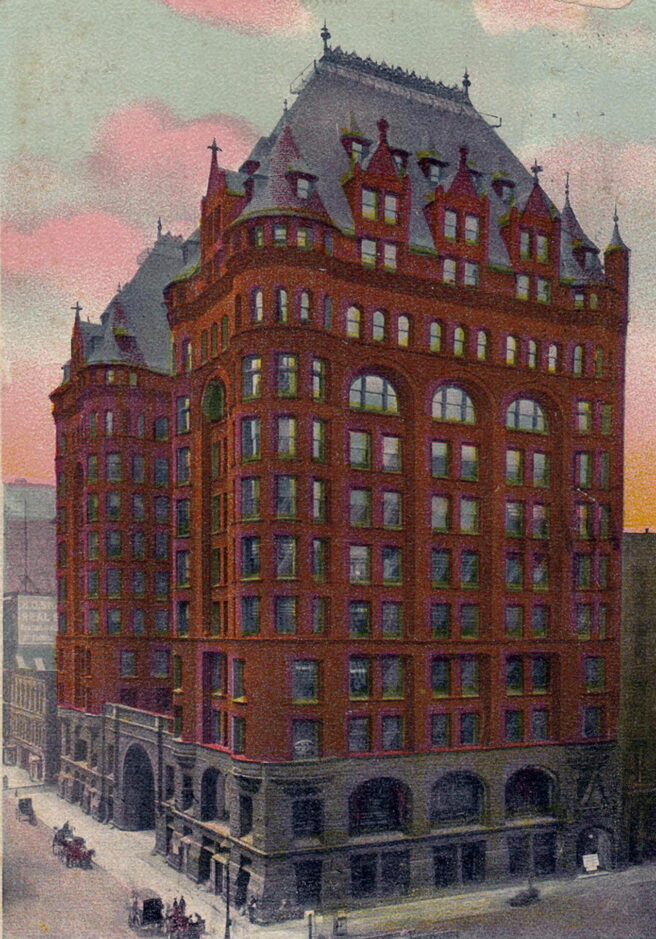

After her death in 1898, Frances Willard left her home, nicknamed “Rest Cottage,” to the WCTU. It was at first unclear what would happen to the house in Evanston. The WCTU’s national headquarters had been located in Chicago’s Loop since 1885; in 1892, the organization had moved into the Woman’s Temple at Monroe and LaSalle. Designed by the architecture firm Burnham and Root, the Woman’s Temple was a 13-story statement in stone and terra cotta, meant to express the strength and influence of the WCTU.

However, the WCTU never owned the Woman’s Temple; the organization leased the offices it occupied in the building. The WCTU distanced itself when the building suffered financial difficulties in the late 1890’s, and when the Woman’s Temple was no longer viable, the WCTU decided to move its headquarters to Rest Cottage. In 1900, two years after Willard’s death, the WCTU held an opening dedication for both the headquarters and the museum, and began its long official history in Evanston.

In 1904, the WCTU built a one-story addition to Rest Cottage to house the “Literature Department” – the publishing arm of the organization. But even with this added space, Rest Cottage was not large enough to hold the WCTU’s publishing operations. In 1910, the WCTU constructed a “Literature Building,” designed by Evanston architect Charles R. Ayars,[1] in the backyard of Rest Cottage. The building served the WCTU during the campaigns for passage of the 18th (Prohibition) and 19th (Woman’s Suffrage) Amendments.

As the WCTU began making plans to celebrate its 50th anniversary in 1924, the “WCTU Jubilee Foundation for the Advancement of Total Abstinence and Prohibition” was created to raise one million dollars for national and international work. Of this, $33,000 was allocated for an addition to the Literature Building to provide office space for national officers as well as more space for the publishing department, since “so rapid and continuous has been the growth of the work of the WCTU in the past few years (due to Prohibition and its enforcement) that a new headquarters building had become an absolute necessity.”[2] Ayars was hired again to design the addition, which echoed the scale and style of the original building, although it was substantially larger.

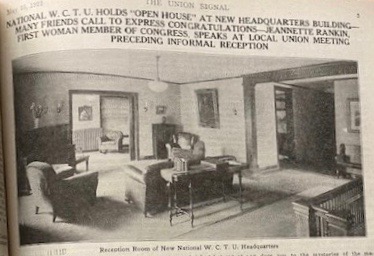

The three-story addition provided two floors of modern office space for WCTU officers and staff, centered around a cozy second-floor lobby with a sun porch. The president’s office, occupied in 1922 by Anna Gordon, fourth president of the WCTU, was located in the southeast corner, directly across from Frances Willard’s “den” (office) in Rest Cottage. The open-plan third floor of the new building was used as classroom space for the WCTU’s leadership training courses, lectures, and children’s activities.

An “Open House” for the new WCTU Administration Building was held on May 19, 1922. Like the Woman’s Temple, the new Administration Building served as a model headquarters for an organization run by women. The building was described as “a substantial yet artistic piece of architecture, manifestly a house built for serious business but withal having a homelike atmosphere not found in the ordinary commercial establishment.” From this new headquarters “the wheels of the WCTU machinery in every state, every county, every local union, begin to turn, and there are set in motion plans of vital moment to the interests of society.”[3]

[1] Ayars was not a stranger to Evanston when he designed these buildings for the WCTU. His family had moved to Evanston in 1883 when he was seven years old and his father had served as president of the village board from 1885-1888. Ayars began his architectural career at the large and prestigious Chicago firm of Holabird and Roche. In 1893 he opened his own firm and over the next forty years built a successful practice with offices in Chicago and Evanston. Along with residential designs, Ayars developed a style for medium-sized public buildings that mixed elements of the commercial style with the size and scale of structures used for educational or organizational purposes. The Literature and Administration buildings both are examples of this style.

[2] Union Signal, May 25, 1922, 5 and 9.

[3] Union Signal, May 25, 1922, 5 and 9.