By Janet Olson

Speaking at a Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) meeting in Evanston in 1883, Mrs. Jennette Hauser posed the title question. It was a logical question—after all, Evanston had been dry since 1855, thanks to Northwestern University’s charter, which stated that no alcohol could be sold within four miles of the University.[1] Since 1855, the new town that grew up around the University had attracted residents and business-owners who were looking for a place to raise and educate their children without exposure to the noxious influences found in alcohol-fueled towns and cities.

Later in her speech, Hauser answered her own question: “Though we give intoxicants no place in our town, our town unfortunately covers little more than one millionth part of a wicked & unfriendly world…”[2]

This blog post marks Women’s History Month, as well as the 150th anniversary of the founding of the Woman’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston in March, 1874. Over the next few months, during this 150th anniversary of the founding of the National WCTU (November, 1874), we will be shining a local spotlight on the Evanston women (and men) who were “early adopters” of the temperance campaign. This joint project of the Evanston Women’s History Project and the Center for Women’s History and Leadership drawsupon the many historical resources available in Evanston to address the rhetorical question that Jennette Hauser posed in 1883.

Part 1: The Woman’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston, founded March 17, 1874

Evanston women, always a progressive and socially conscious force in the town, had been galvanized by the reports from around the country about the Women’s Crusades against alcohol. Beginning in December, 1873, in towns in New York and Ohio, the Crusades inspired respectable church-going women across the U.S. to step out of their traditional roles and take to the streets, boldly entering or gathering outside saloons, drugstores, and hotels to shame drinkers into going home and—most important—persuading purveyors of alcohol to stop selling.[3]

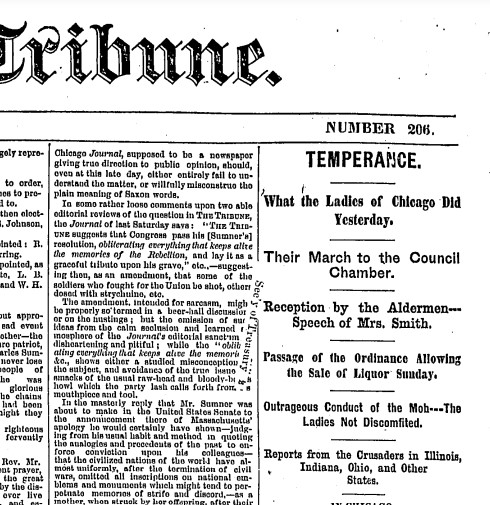

From winter through spring, 1874, local and big-city papers spread the news of the surprising uprising of formerly well-behaved women. Four miles south of Evanston, the wicked and unfriendly city of Chicago saw the repercussions of the crusades as women lobbied the City Council to maintain its ban on Sunday saloon openings. The women who led the lobbying crusade were teased, harassed, and insulted by crowds of dissenters—mostly men. Despite the 14,000-signature petition which the crusading women braved “the mob” to present to the City, the effort to keep the Sunday ban failed.

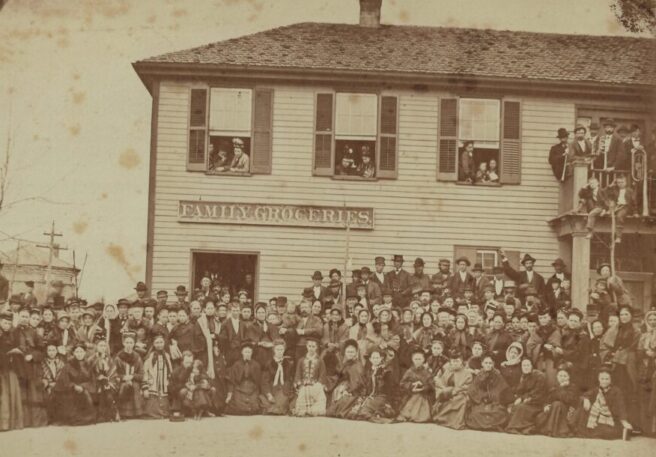

The Chicago Tribune reported on the gory details of the failed crusade in articles on March 14-17, while praising the women for their courage.[4] The reports from Chicago had a motivating effect on the women of temperate Evanston, who immediately sprang into action on March 17. The Evanston Index reported on the formation of the Women’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston, noting that “The meeting of ladies at Union Hall [on Davis Street] last Tuesday afternoon was attended by many of the best ladies of Evanston,” representing a range of Evanston churches—Baptist, Congregational, Presbyterian, Episcopal, Catholic, and of course Methodist.[5]

The meeting was called to unite the women of Evanston on behalf of the temperance cause. Mrs. Charles Browne talked about “the Chicago mob”: her own sister had been among the women who were “insulted by those ruffians,” and she hoped that “the rebound of that disgraceful proceeding might do good in arousing the Chicago people to the dangers which threaten them.” The women’s first order of business was to produce a resolution of hearty sympathy with the women who had faced “the first fire of their enemy on the streets of Chicago.”[6]

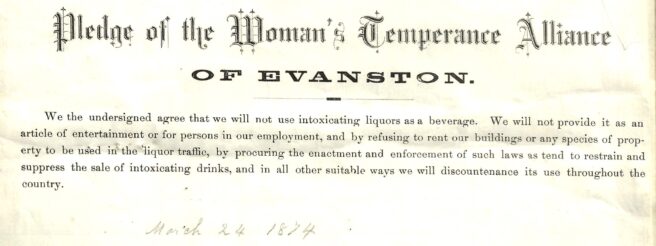

The goal for the new organization was to focus on Evanston, stirring up public sentiment against alcohol by launching a campaign to get every citizen to sign the temperance pledge–or be disgraced in their neighbors’ eyes. Aside from the moral example of “pledging the town,” and despite Evanston’s dry laws, there was a need for an organization to address “the prosecution of violators of the university charter law,…and the visiting of all places within the four-mile limit where liquors were secretly sold or gaming was carried on.”[7]

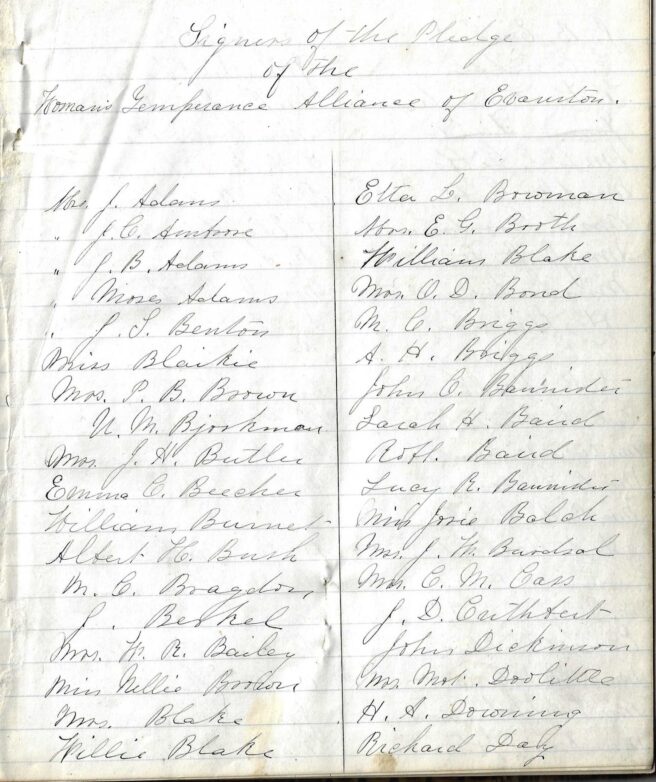

As we will see later in this series, over 700 names appear on the list of Evanston residents who eventually signed the Alliance’s temperance pledge.[8] Signers include women, children, and men—sometimes whole families—reflecting a roll call of early Evanston names from Adams to Woodruff. An addendum included the names of 54 women and men from the University. However, the leadership of the Alliance was held by women (many of whom are included in the Evanston Women’s History Project database).

More details about the work of the Woman’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston will be revealed in our next installment, which will focus on the contributions of Elizabeth Marcy, the president of the new Alliance. She was active in Methodist missionary and settlement organizations, and was the wife of NU professor/interim president Dr. Oliver Marcy.

Note: Sources for this series come from several Evanston institutions, including the Center for Women’s History and Leadership (CWHL), Evanston History Center (EHC), Evanston Public Library (EPL), Northwestern University Archives (NU), and the WCTU Archives (WCTU)

[1] The amendment establishing the 4-mile limit is at https://www.northwestern.edu/about/board-of-trustees/docs/university-charter.pdf, p 4, 1st amendment to the charter. NU

[2] “Speech by Mrs. Hauser,” Box 1, Folder 5, Records of the Evanston WCTU, 1874-1992, WCTU Archives.

[3] See Kristin Jacobsen’s blog post about the Women’s Crusades on the CWHL website

[4] See the Chicago Tribune issues from March 14-16, 1874. During this time, Frances Willard, embroiled in challenges at the Woman’s College of Northwestern University, did not get involved, but, as she said in her autobiography, “while we were musing, the fire burned” (Glimpses of Fifty Years, p. 336). Her sister-in-law, Mary B. Willard, was a founding member of the Woman’s Temperance Alliance.

[5] “Temperance,” Evanston Index (March 21, 1874), page 2. The digitized newspaper is available at EPL.

[6] “Temperance,” Evanston Index (March 21, 1874), page 2

[7] Frances Willard, A Classic Town: The Story of Evanston (Chicago: Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, 1891), page 169; this book is digitized and available on the Internet Archive, as well as in hard copy. Additional information about the formation of the Alliance is in Robert D. Sheppard and Harvey B. Hurd, History of Northwestern University and Evanston (Chicago: Munsell Publishing Company, 1906), pp 395-397. This book is available digitized on the Internet Archive—as well as in hard copy.

[8] “Ledger of the Woman’s Temperance Alliance of Evanston and WCTU, 1874-1881,” Box 1, folder 7, Records of the Evanston WCTU, 1874-1992, WCTU Archives