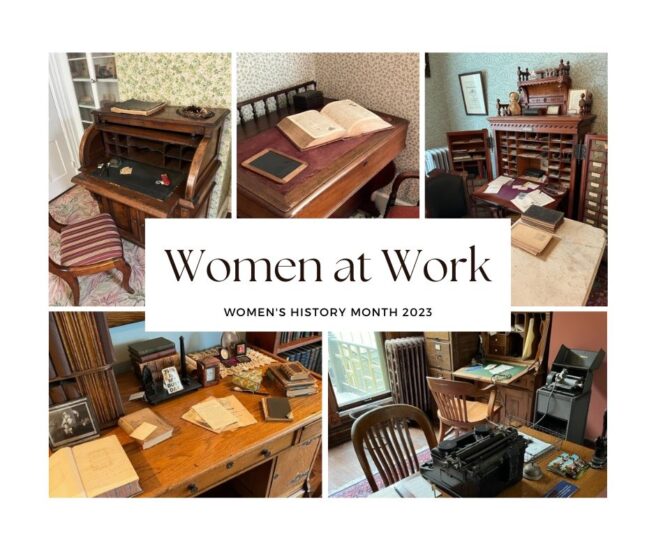

Happy Women’s History Month! This year we are featuring items in our collection where a closer look reveals a hidden story. For Women’s History Month 2023, our theme is Women At Work, and the stories that the desks in the Willard House reveal will be our focus.

Mary Thompson Hill Willard’s desk

Found in her upstairs bedroom, this small desk was the scene of much activity. Whether reading and clipping newspapers, keeping track of the household accounts, corresponding with friends and family near and far, or creating dozens of scrapbooks documenting her famous daughter’s exploits – Mary Thompson Hill Willard was busy at work at this desk.

Mary Willard has an interesting story all her own. Born in upstate New York, she worked as a school teacher before her marriage. As a young mother, she attended college courses at Oberlin College. In rural Wisconsin, where the family later moved, she was her children’s primary teacher and great champion. She served in this latter role throughout Frances Willard’s life. Willard later wrote a book about her called A Great Mother documenting the many ways Mary Willard offered her – and others – support and encouragement.

The work of running a family is often hidden in our homes – and at historic house museums. Homes were (and often still are) the primary workplaces for women. Mary Hill Willard’s desk can reveal this story if we look more closely. You can read more about Mary Hill Willard’s life and work here.

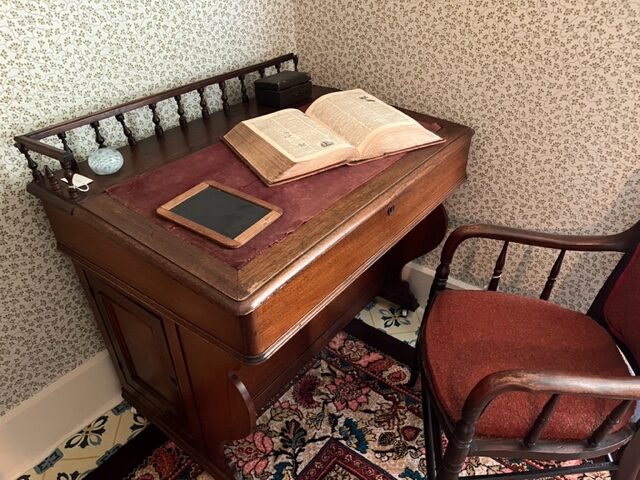

Frances Willard’s desk from Northwestern University

In 1871, Frances Willard became the President of a new women’s college, the Evanston College for Ladies. She served as its president for two years. When it merged with Northwestern University in 1873, she became NU’s first Dean of Women and served in this post for another year. The fraught story of these three years, the last years of Willard’s career as an educator, can be found in a series of posts on our blog.

This small desk (now in Willard’s bedroom) was used by her during the years she worked for the Evanston College for Ladies, and afterwards for Northwestern. From here she wrote fundraising requests to benefactors of the college, graded papers for the classes she taught (with both male and female students), monitored her students’ behavior through their “self-reports,” and wrote lectures and speeches she regularly gave as she developed her public speaking career. She also penned her 25-page letter of resignation here when she left the university in the spring of 1874.

Willard’s time as an educator allowed her to build on skills that would be critical to her later work. But it also proved frustrating when she encountered the limits of working in institutions primarily governed by men. Her shift to work as a reformer – and for an organization entirely run by women – opened up the world to her.

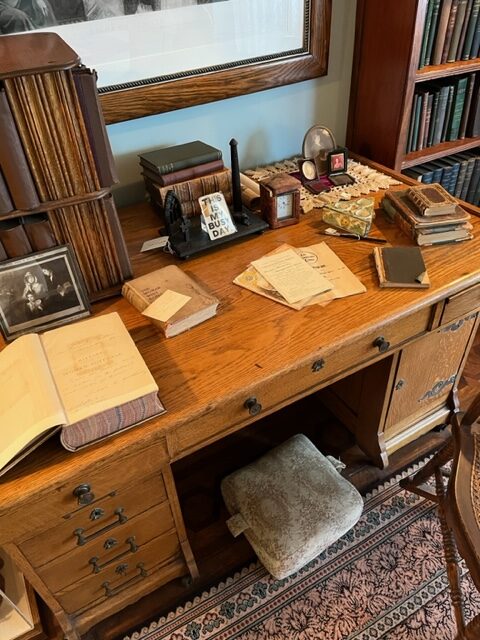

Frances Willard’s desk from WCTU years

Frances Willard’s career as a social reformer began in 1874 when she joined the newly founded Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and was elected Corresponding Secretary. Five years later she was elected President of the WCTU. Her upstairs office was the center of her busy “Do Everything” working life. From here she advocated for temperance and many other reforms including woman’s suffrage, the 8-hour workday, stricter age of consent laws, and women’s inclusion in church ministry. The “Do Everything” list is a long one.

The desk in her upstairs office (the room was remodeled for her in 1890) was where she wrote about all these issues in her many speeches, newspaper articles and essays; strategized for local, state, National and World WCTU meetings; and corresponded with dozens of colleagues, friends and family members.

By this time, she was assisted by many other women working with and for her, near and far. From this desk in particular she would have directed the work of stenographers, typewriters and editors who worked in other offices in the house, managing the many tasks that made her high work production levels, and the expansive reforms that the WCTU advocated for, possible. She also would have had regular meetings with her personal assistant, Anna Gordon.

Anna Gordon’s desk

This “Wooten” desk belonged to Anna Gordon, Willard’s close friend and coworker. Willard met Gordon at a WCTU meeting in Boston in 1877 and quickly realized how valuable the younger Gordon could be as a personal assistant. Gordon came to Evanston and stayed at Willard’s side for the rest of her life.

From this desk, Gordon managed Willard’s busy schedule, coordinated their travels, organized the annual WCTU conventions, and corresponded with colleagues, family and friends, both her own and Willard’s. The desk was a gift to Willard but it did not match her working style, with all its little labeled cubbies, so the desk was given to Gordon and used by her for the rest of her life.

After Willard’s death in 1898, Gordon ran the house as the WCTU headquarters and museum. Gordon was the fourth president of the WCTU, serving from 1914 to 1925 – when both the 18th (Prohibition) and the 19th (Suffrage) amendments were ratified. She died in 1932.

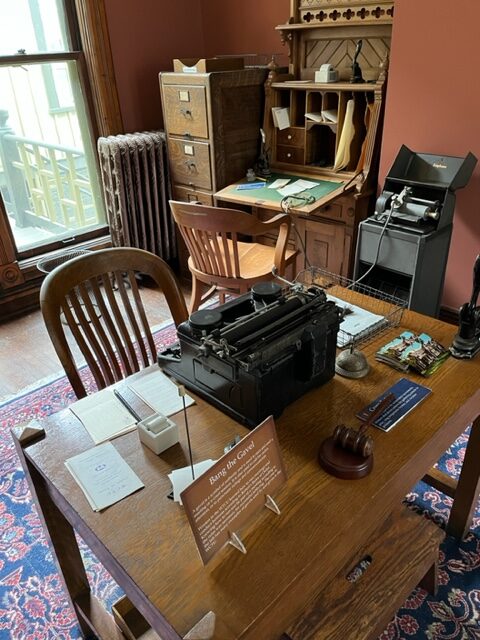

WCTU Headquarters office

Though nicknamed “Rest Cottage” we know that the Willard House was often far from a restful place. Willard filled its rooms with coworkers in the WCTU early, calling the house an “annex” to the actual headquarters in The Woman’s Temple, a beautiful downtown Chicago office building built for them by architect Daniel Burnham. After her death in 1898 the WCTU leadership decided to retreat to Evanston, finding its new footing without her in her home. In 1900, the Willard House was transformed into their national headquarters and a museum to honor her.

Today, we have interpreted this time period with a recreation of one of the offices in the home. We know from photographs and other documentation that these rooms were used to manage the WCTU’s membership and publication efforts from 1900 through 1922. These were especially busy years as the organization was leading the way on two constitutional amendments, the 18th (Prohibition) and the 19th (women’s suffrage).

As we close Women’s History Month 2023 we remember that homes are work spaces – even those that did not function as organizational headquarters – and that often the work that took place within their walls remains hidden but so important to reveal.