By Lori Osborne, Frances Willard House Museum Director

See Part 1 here for the beginning of the story.

North Western Female College thrived in its early years, despite the setbacks of losing its first building to a fire and the multi-year absence of founder William Jones for health issues. It established Evanston as a place where educated women could find a home and where women’s education was important. In 1869, Northwestern University’s new president, Erastus Haven (formerly president of the University of Michigan) brought modern ideas about women’s education. Northwestern resolved to admit women students “on the same terms”[i] as men. In June, 1869 the school became co-educational when three female students enrolled.

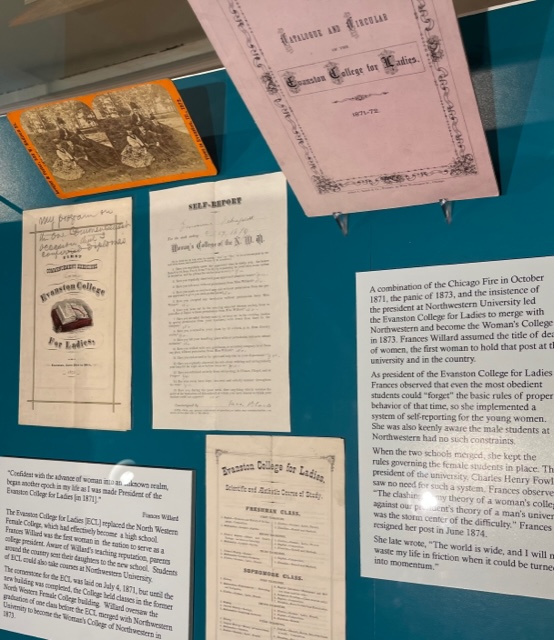

In 1871, a group of Evanston women, led by education advocate Mary Haskin[ii], approached William Jones about the future of North Western Female College now that Northwestern was co-educational. Creating a connection between the two schools seemed the right next step to ensure the success of the whole project. They proposed that NWFC merge with a new institution, the Evanston College for Ladies (ECL), which would serve as a “sister” college for the university. The concept of a “sister” women’s college, usually affiliated with an all-male school, offering shared courses but separate administration and housing for the women, had been pioneered at Vassar, and seemed an ideal model for the new college in Evanston.

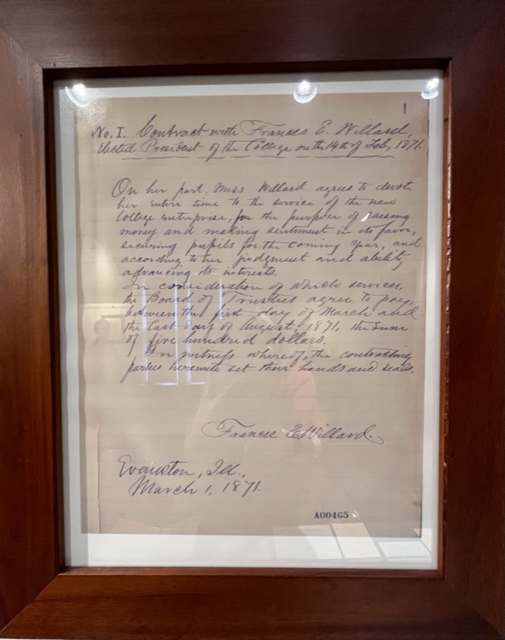

Haskin recruited the new school’s leadership from among her Evanston friends and associates – establishing the country’s first all-female board and all-female staff to run an all-female college. Haskin “believed that women should be a felt force in higher education, not only as students, but as professors and trustees.”[iii] Frances Willard was hired as the first President of the Evanston College for Ladies. With this organization in place, Jones agreed to transfer his beloved project to the Woman’s Education Association, and NWFC had its final graduation ceremony in June of 1871.

Willard spent her first months organizing a rousing “Woman’s Fourth of July” fundraising campaign[iv], bringing in $30,000 in pledges toward the construction of a new building. Ground was broken that day on park land at Orrington and Clark Street, given to the ECL by the town of Evanston. With 236 women enrolled in the new school, the ECL had ambitious plans for a first rate education for women with the option of taking additional classes at Northwestern.

Still, the auspicious start of the school in September of 1871 was accompanied by daunting questions – how to fund scholarships for women who wanted to attend but could not afford tuition; where to house them; how best to connect female students to the university while remaining separate; how best to supervise them under this new model; and how to convince parents to send their daughters to a co-educational school. It was still early in the project of educating women and there was much to be figured out.

To address some of the financial issues, Haskin and her board formed a fundraising arm called the Women’s Educational Aid Association (WEAA). The WEAA raised money to support female students on the “Mount Holyoke plan” where students did housekeeping tasks in exchange for room and board, living in two small dormitories – College Cottage and, later, Chapin Hall.[v]

As President, Willard developed a structure for the girls’ education and for their daily lives, including a model for “self-assessment” that put the girls in charge of their own behavior under a strict set of boundaries she monitored. Willard also worked harmoniously with NU president Haven – and was herself on the front lines of the co-education experiment as a professor at the university, teaching both male and female students.

Despite its success in attracting students and raising money, the new college suffered a serious setback in its first years. In October, 1871, just three months after the July 4 fundraiser, the Great Chicago Fire threatened the funds that had been pledged. At the time, it appeared to be a temporary financial crisis, and for the next year and half, Willard and the ECL trustees struggled to adapt to this unanticipated circumstance.

In November of 1872, Northwestern said goodbye to Erastus Haven and welcomed Charles Henry Fowler as its new president. Willard and Fowler knew each other from his days as a student at Garrett Seminary and friendship with her older brother Oliver. They were even engaged for a short time in 1862, and though she had broken off the engagement, they had remained friendly.

Meanwhile, the ECL, now in its second year, seemed to be thriving. The Evanston Index newspaper reported in December:

“The Winter Term of the Ladies College begins next Monday, Dec 2nd. The attendance will be full as during the fall term. Every department of the college is in a flourishing condition.”

It also reported on a visit and lecture by Elizabeth Cady Stanton who “pronounced our Ladies’ College ‘the most advanced of any on record in the working out of co-education theory.’”[vi]

But over the course of the 1872 school year, the financial fallout from the fire and the burden of raising funds for the new building came to a head. After much discussion, the WEA finally decided that the best thing would be to fully merge with Northwestern. The Evanston College for Ladies held its first and final commencement in June of 1873 after just two full years of operation.

In September of 1873, the Woman’s College of Northwestern officially opened with Willard as the first Dean of Women and Professor of Aesthetics. Per the terms of the merger, several women who had served as ECL Trustees were added to the University Board of Trustees, a first for the university. The new college building was finally completed with Northwestern’s funding and women moved in starting in the winter term of 1874 (the building still stands at 711 Elgin.). In June, 1874, Sarah Rebecca Roland became the first woman to graduate from Northwestern.

The early story of women’s education ends here with Northwestern University becoming fully co-educational. The effort for Northwestern’s women students (and faculty) to obtain an educational experience equal to that of the men continued to evolve and face challenges into the present, but the story is commemorated in Evanston by the still-impressive and elegant building at 711 Elgin, for which the cornerstone had been laid by the WEA for the Evanston College for Ladies in July, 1871.

[i] Quote from the Northwestern University Board of Trustees minutes, June 23, 1869.

[ii] See more about Haskin at https://evanstonwomen.org/woman/mary-f-haskin/.

[iii] From Glimpses of Fifty Years, Frances Willard’s autobiography, p. 199.

[iv] See our blog post about the event: https://cwhlevanston.org/1099-2/.

[v] The WEAA still exists to support women students at NU, although it no longer administers housing.

[vi] Evanston Index, Dec 7, 1872 p.3 and Dec 21, 1872 p. 4.