By Fiona Maxwell

Director of Museum Operations and Communications, Frances Willard House Museum

History PhD candidate, University of Chicago

In recognition of the 150th anniversary of Frances Willard’s role as President of the Evanston College for Ladies (1871-1873) and Dean of Women at Northwestern University (1873-1874), the Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU Archives is exploring the history – and the prehistory – of women’s higher education in Evanston. This is the second installment in a series of blog posts about Willard’s educational experiences. You can read part one here.

On March 2, 1858, Frances and Mary Eliza Willard woke up at three o’clock in the morning, bade farewell to their beloved “Forest Home” in Wisconsin, and embarked on an hours-long train journey to Evanston. By late afternoon, the teenaged girls caught their first glimpse of the Northwestern Female College. “It is a beautiful building,” Mary Eliza scrawled in her journal. “Hope, and guess, we shall like to live here.”

Frances Willard later reflected that the curriculum she and her sister encountered – “a woman’s college course equal to that arranged for young men” – was “practically unheard of.” When the Northwestern Female College “quietly took its place” in the region’s educational landscape in 1855, it was “met with disgust and scorn by many good, influential, and wealthy men” who objected to associating “the sacred name of ‘college’ with the unscholarly name of woman.” Nevertheless, the stubborn little school had come to stay.

At the Northwestern Female College, Frances Willard joined a community of women faculty and students who, like her, possessed “literary ambition.” During her college years, Willard rehearsed skills in public speaking, writing, and leadership that she would eventually use to mentor other women and advocate for reform on the world stage.

The Northwestern Female College curriculum placed unique emphasis on developing young women’s speaking skills. At other institutions, women students composed their essays in silence and occasionally listened to male professors read them aloud. The Willard sisters, by contrast, began training in elocution on their first day. Mary Eliza effused to her diary: “I spoke in class to-day, the first time I ever did such a thing in my life,” and when Frances began to speak, her “shyness and apparent indifference melted away” and her face shone with “enthusiasm.” As soon as Frances finished, her classmates whispered to one another: “My! can’t she recite?”

The Northwestern Female College was replete with extracurricular speaking opportunities, and the Willard girls took full advantage. Frances attended lectures by renowned visiting speakers and jotted down the components of successful performances in her journal. She put these strategies into practice at the open sessions of the students’ Minerva Society, which were filled with debates, essays, and literary papers. The end-of-term “grammar party” – which Frances described as “the great day of the year” – challenged young women to speak in front of and with young men from the neighboring Northwestern University. After listening to William P. Jones, the President of the Northwestern Female College, give a “witty speech” on “the importance of language,” students honed conversational skills, played dramatic games, and performed original compositions.

Frances and Mary Eliza were invited to speak at Commencement at the end of their first term, and Frances reveled in the chance to demonstrate her growing proficiency. Standing “under a beautiful arch” on an “immense stage” built for the occasion in the Methodist church, she delivered an original essay, experiencing an “inward tumult of delight as the bouquets from all parts of the house fell at my feet.”

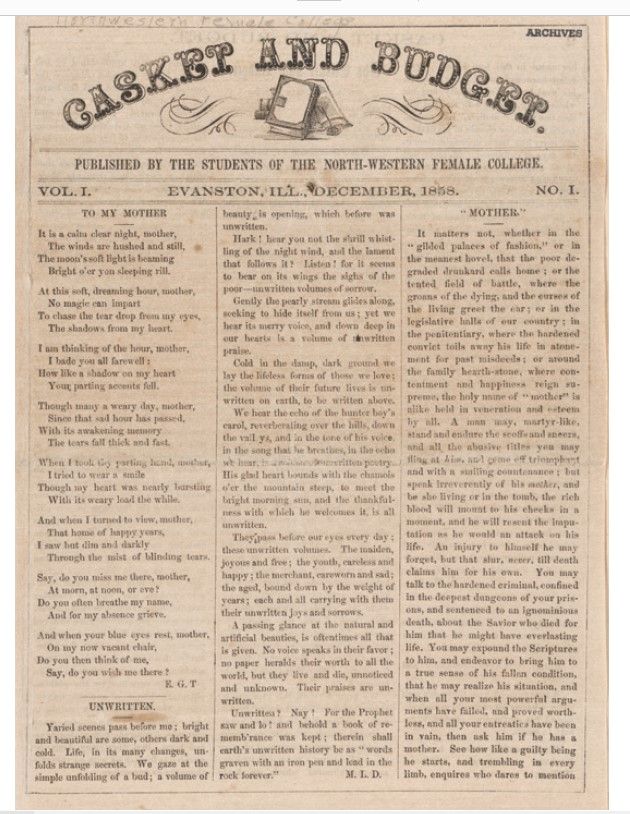

Willard’s charisma led her to become, in the estimation of her classmates, the “leader of all the intellectual forces among the students.” She served as “editress” of the Casket and Budget, the student newspaper, and oversaw the Department of Notes and Queries of the Iota Omega society, proving “never more herself” than when directing her clubmates to “hunt for some valuable bits of information.” President Jones observed that the other students “loved to cluster around her and hear her talk,” as Willard “set them to discoursing on subjects quite out of the ordinary” and interspersed “her own wise, quaint and witty speeches, to the great delight of her listeners.”

Willard rooted her leadership style in a sense of play and humor. While on the surface she was a “carefully dressed, neatly gloved lady who took the highest credit marks in recitation,” she also possessed a “happy-go-lucky, reckless spirit of adventure” and, perhaps surprisingly, became “ranked with the ‘Ne-er-do-weels.’” Frank, as she was called by her chums, along with her partner in crime Maggie, the “wildest girl in school,” found creative ways to evade the college’s seventy rules, such as by perching “in the steeple of the college building” during study hours, “unbeknown to the authorities.” Frank and Maggie’s most memorable moment of mischief occurred when, inspired by Jack Sheppard – “the greatest of pirate stories,” in Willard’s estimation – the girls dressed up as pirates and set to work “planning for the adventures that were before us as highwaymen of the sea.” Getting in character required using as much foul language as they knew – “which was not much,” Willard admitted – donning “high-top boots,” arming themselves with “wooden pistols and bowie-knives,” procuring “a cigar apiece,” and splitting “a bottle of ginger-pop, which was as far as we dared to go in the direction of inebriation.”

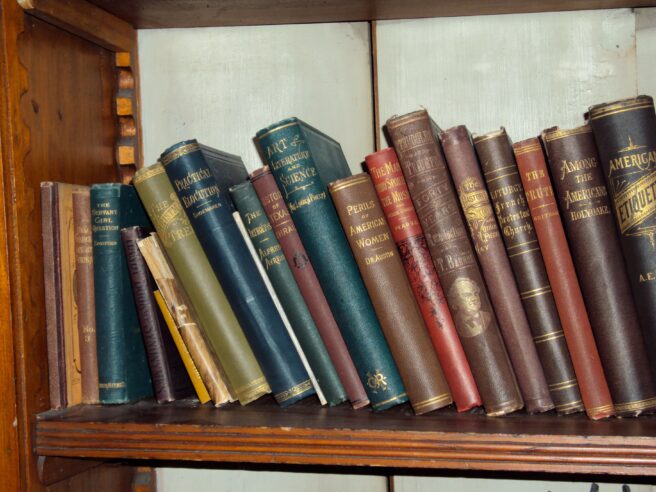

During Willard’s second and final year, she became increasingly devoted to her studies. Living at her family’s new house in Evanston, she spent many hours “alone at home, deep in a young girl’s philosophy of existence.” Preferring to spend her free time with her “equals, and companions,” she felt uncomfortable interacting with the town’s social elite. This, she confided in her journal, was “why I like books so well.” Unlike her “superiors in position, age, or education,” books were “great without arrogance, wise without hauteur.” “To books, then, let me flee,” Willard decided.

Immersing herself in books helped Willard clarify her thoughts on gender roles. She tracked “ideas about a wife’s obeying her husband” in everything she read, from the Bible to serial fiction. She wrote that while her opinion “may seem wrong to others,” it was “my way of thinking, and I have a right to it. That right I will maintain.” Reading also introduced Willard to a female role model: Margaret Fuller Ossoli. “Here we see what a woman achieved for herself,” Willard wrote of Ossoli’s Memoirs. She asked her journal: “If she, why not we, by steady toil?”

Willard’s final year was “one of unceasing application.” She woke up at four in the morning to study, only to be found by her family members asleep in the parlor, face resting on her open textbook. The faculty voted Willard valedictorian, but just before graduation she fell ill with typhoid fever. She was unable to attend Commencement and give her valedictory address – “the great disappointment of my life,” she lamented. Still, as she convalesced, she reflected that she and her brother Oliver had both received their diplomas. “We are graduates!” she exclaimed. “How very little does the word mean, and yet how much! It means that we have started on the beautiful search after truth and right and peace. Only started – only opened the door.”

Willard looked forward to the next stage of her educational journey with great anticipation. While she “truly” loved knowledge, she was “glad to leave school” because she felt ready to direct her own learning “free from a restraint that is irksome to me.” When her former schoolmates “visited her in her quiet little room,” they “found her always at her desk with books, paper and pen.” But Willard hungered for a purpose beyond satisfying her own intellectual curiosity. Praying that her “life may be valuable,” she vowed to “earn my own living” and “try to be of use to the world.”

The Northwestern Female College encouraged young women to empower themselves and one another through the spoken and written word. President Jones recalled that as a student Willard’s “lively imagination drew plans for the future, not only of herself but of those around her.” Through their classes, performances, and conversations, Jones believed, Willard and her schoolmates “laid foundations for character and future achievement.” In the decades to come, Willard would invite countless women to envision and work towards a better future through collective political action. But in 1859, she had a different career path in mind. “I believe that to be connected in some capacity with a school is what I am intended for,” she predicted. After working for twelve years as a “roving teacher” across Illinois, Pennsylvania, and New York, in 1871 she was invited to assume charge of her Alma Mater. This homecoming marked a new chapter in Willard’s personal trajectory and in the history of women’s higher education.

All quotes are from Frances Willard, “College Days,” Glimpses of Fifty Years: The Autobiography of an American Woman (Chicago: Woman’s Temperance Publication Association, 1889).