By Fiona Maxwell

Director of Museum Operations and Communications, Frances Willard House Museum

History PhD candidate, University of Chicago

In recognition of the 150th anniversary of Frances Willard’s role as President of the Evanston College for Ladies (1871-1873) and Dean of Women at Northwestern University (1873-1874), the Frances Willard House Museum and WCTU Archives is exploring the history – and the prehistory – of women’s higher education in Evanston. This is the first installment in a series of blog posts about Willard’s educational experiences. You can read part two here.

In 1854, Frances Willard was full of “imaginings” about what she “was to be and to do in the world.” By the age of fourteen, she had become “fully persuaded” that “something quite out of the common lot” awaited her, but her ideas were “vague as to the what and the why” because “women were allowed to do so few things.” Taking stock of her interests and skills, she determined “that I wanted to write, and that I would speak in public if I dared – though I didn’t say this last, not even to mother.”

For women of Willard’s generation, writing and speaking represented the practical tools necessary to open new professional paths and to make their voices heard in the public sphere. Despite sparse opportunities for formal education, as a young girl Willard learned to connect the pursuit of knowledge and self-expression to personal and societal transformation. When she was twelve, her father brought home a card containing the Latin words for “Knowledge is power.” “Very many times I said them over to myself,” she recalled, “much more I thought about them, seriously determining that I would attain knowledge so far as in me lay.”

Growing up on an isolated farm near Janesville, Wisconsin, Willard’s earliest education was superintended by her mother. Mary Thompson Hill Willard’s “dearest wish” was for her children to become “well educated,” and she told them that the most important skill to learn was “the power of expression,” namely, “how to speak and write.” Apart from her instruction at “her mother’s knee,” Frances devoured endless stories and historical pieces to learn “what sort of world was this of which I had become a resident.” When her father took her to town, she liked nothing better than to visit the bookstore, as “the very presence of books was a heart’s ease,” and she always “felt at home where books were kept.”

Beyond developing a voracious appetite for reading, Willard became an avid writer. Every day she climbed to a “high perch in the old oak tree” to “write down the day’s proceedings, scribble sketches and verses,” and work on her never-ending novel, Rupert Melville and His Comrades: A Story of Adventure. She shared her productions with anyone who would listen, reading each one aloud “as fast as it was written.” By the time she was a young teenager, she determined that “write I could and should and would.”

Willard’s penchant for scribbling was matched by her desire to speak. When the Willards were living in Oberlin, Ohio, three-year-old Frances watched the college students “rehearsing their speeches and would get up an amusing imitation of them.” Her parents encouraged her performative impulses by standing her up on a chair and having her recite poetry for guests after dinner. Her father always demanded “something feminine, or else nothing at all,” but her mother encouraged Frances to experiment with a variety of styles and genres.

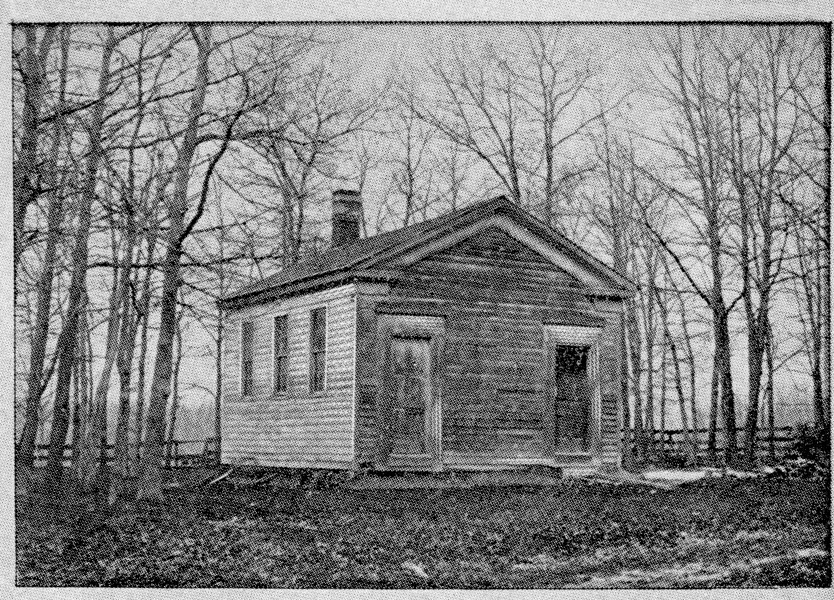

When Frances turned twelve, her mother determined that she needed more formal instruction. While her father worked to bring a schoolhouse to the district, her mother decided to “fit up the parlor” as a temporary classroom and hired Rachel Burdick, a young woman “of rare accomplishments,” to teach a small group of neighborhood girls. At the end of term, Willard and her three classmates “gave an elaborate ‘Exhibition’” which seemed to them as “great” in importance as the Commencement exercises of a university. Finally, when Frances was fourteen, a one-room schoolhouse was built near her farm. She idolized the little school as “a temple a learning, a telescope through which we were to take our first real peep at the world outside of home,” and regarded her first day as “the great event of my life,” as it marked her initiation as a true “scholar.”

Throughout her youth, Willard persistently pursued her makeshift education, whether guided by her mother, her neighbors, or herself; whether studying in the parlor, the schoolhouse, or up a tree. Nevertheless, due to her gender, her next steps were frustratingly undefined. Willard’s parents had always planned for Frances’s older brother Oliver to go to college, but “the fate of his sisters was more misty.” Frances and her family regularly attended the Commencement exercises at Beloit College, and when Oliver turned eighteen, he left home to attend the school. Frances bemoaned that “now ‘Ollie’ was to go, and sometime he would be a part of all this pageant, but not the girls,” an injustice that gave her “long, long thoughts.”

When Willard turned seventeen, several developments coalesced to open her eyes to gender inequality. She had to put up her hair and wear long dresses, which brought an end to her active and imaginative outdoor play. She also watched her brother go off to vote for the first time and harbored deep distress at the thought that, as a woman, her vote would never count. She grew so restless that she began to formulate plans to run away. Confessing her intentions to her mother and sister, her mother identified higher education as the path forward. The women of the family gave Frances’s father “blessed little peace” until he arranged for Frances and her sister Mary to attend the Milwaukee Female College. There they took part in a series of closing exercises, in which Frances learned to ascend a public platform and speak her own words “loud enough to be heard throughout the room.”

The following year brought an exhilarating culmination to Willard’s aspirations. The Willards learned of the Northwestern Female College, located in Evanston, Illinois, “the only woman’s college of high grade” and the only one that possessed a curriculum “almost identical” to its neighboring all-male university. When the family left their Wisconsin farm in 1858 in search of the “educational advantages” of Evanston, Willard’s ideas for what she “was to be and to do in the world” soon lost their vagueness and become concrete realities. As a beneficiary, and eventually an architect, of Evanston’s unique experiments in women’s higher education, Willard would grow from a student, to a teacher, to a world-renowned writer, orator, and advocate for women’s rights.